Around the time Didier Fiuza Faustino initiated his double practice as an architect and artist, Jonathan Hill proposed the notion of the 'illegal architect' as one who "questions and subverts the conventions, codes and 'laws' of architecture." Only partially interested in the unqualified builder outside the professional field, Hill was concerned with those practitioners who worked in the borders of architecture and, yet, were the "most likely to value the user and transform architectural practice."

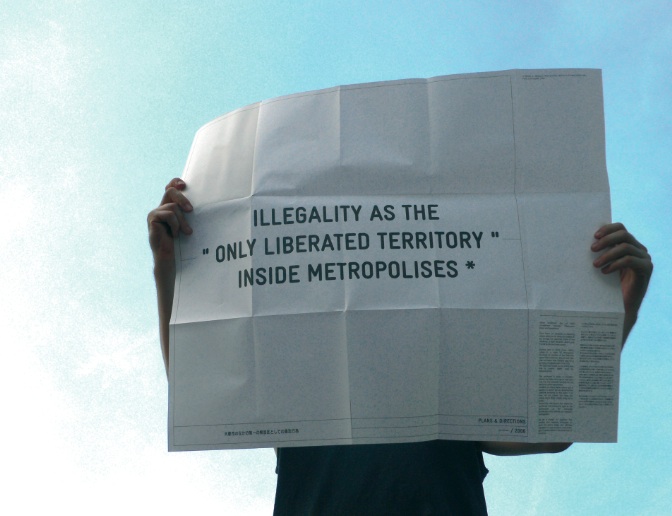

Ten years later, Didier Fiuza Faustino participated in the Venice Architecture Biennale with a provocative manifesto. A black-and-white poster pinned to the wall alleged "illegality as the only liberated territory inside metropolises." Faustino spoke from legitimated grounds, but his statement rightly crowned a zigzagging career in which architecture's lawful territory was put into question. Jumping from the domain of art to that of architecture and back again, Faustino played on the fringe of both these fields so as to create a distinctive, impermanent site from where he could perform a highly personal, critical form of architectural commentary.

Bordering on illegal territories, Faustino found a way to transform architecture into a liberated zone of political action. Exploring the formal and mental boundaries of his field of practice, he managed to expand the ability of architecture to return to the real with its own meaningful, powerful micro-narratives. In 2008, for example, Faustino proposed an experiential reenactment of the "often ambiguous zone of limit between public and private space." Redefining the boundaries of the Storefront for Art and Architecture through the use of a chain-link fence that meandered in an out of the building, Faustino not only confused the institutional limits of the gallery space, but he also obliged the visitors to perform acts of true contortionism so as to access the gallery. As if commenting on the borders of cultural fields themselves, he suggested that the struggle to gain right of entry to certain territories of practice is complex and even eventually painful.

When one year later he again recurred to the chain-link for his Point Break installation at the Laxart gallery in Los Angeles (2009), he made the metaphorical use of this material more overtly political. He extended his architectural commentary to the everyday appropriation of urban space, alluding to the nearby illegal emigration or the militarized fields where refuges and political prisoners are kept. As the installation of the fence was taken to an exquisite degree of aesthetical sublime, so its impression on the spectator was one of looping the preconceived banality of those fragile, yet imposing borders.

When referring to the work of artists like Dan Graham, James Turrell or Rebecca Horn, Hill had already suggested that 'illegal architecture' does often "occur in a border." Like San Diego-based Teddy Cruz, Faustino is thus attracted to these sites of "spatial flux," filled with their own "thickness." Borders become, in his case, privileged vantage points from where to observe, and perhaps assault, the adjacent territories of cultural and urban production.

Pierre Bourdieu famously argued that cultural domains are highly disputed. Exploring their borders becomes, as such, an essential asset for a tactical positioning vis-à-vis the available positions of a given field and the possibilities of its political transformation. Indeed, if the challengers of the architecture field want to "impose new modes of thought and expression, out of key with the prevailing modes of thought and with the doxa," they might want to start with testing the boundaries of the accepted modes of acting within the profession. In order to establish a vantage point and his own terrain within the architecture field, Faustino used his knowledge of art to question the boundaries of architecture; and, inversely he used his architectural skills to expand the confines of art. This double agency became a useful tactic towards what French anthropologist Michel de Certeau precisely called débordement.

While constantly hopping in-between two fields - and while remaining at the fringes of mainstream practice - Faustino is able to momentarily acquire positions of legitimacy from where to destabilize and undermine the conventional authority of architecture. The 'illegality' of his practice becomes a form of liberation, while it also allows for his urban interventions and performative architectures to bear an unusual critical content. In his public space installation Stairway to Heaven (2002), for instance, Faustino extracted the symbolic insides of a banal suburban building and rebuilt it in public space as an unexpected monument to solitary play.

The standalone concrete stairway leads onto a private stage for basketball, and becomes a device for a dual surveillance. The strange hybrid object disturbs the fragile social borders of private and public, it upsets the rationale of the modernist urban standardization, but moreover it displaces the expected limits of architectural functions and their standard forms. The Stairway operates a string of débordements. Moreover, this structure acquires its full meaning only when its use is displayed as a core narrative, its intense criticality thus drawn close to the emerging notion of performance architecture.

As architects again welcome narratives of use -- happenings, events, actions, community participation, etc. -- into the very constitution of their temporary, some times unsolicited interventions within the urban arena, performance architecture is becoming a political practice that upsets the previous notion of architecture as an uncritical social service achieved through more or less permanent building. Performance art once "represented a kind of activism that had as much to do with agitating the commodity-oriented mechanisms that drive the art world as with exploring new crossover relationship with other media." Now, performance architecture sees the (re)birth of the architect as a social critic and an activist operating in an expanded spatial field. It pushes the established borders of a proper professional practice, while providing for the return of the other of modern architecture: the user.

In Stairway to Heaven, the performance of a perfectly rationalized production -- like Henri Lefebvre would label the modernist machine a habiter -- is substituted by an other kind of performance: the ghostly act of a single body that calls into question the physical and psychological balance of today's urban settings and their corresponding, paradoxical individualism.

In other recent works by Faustino, such as Hand Architecture (2009), performance is ironically proposed as the escape route for an architecture that is increasingly seen trapped inside its own armored body. With its 'illegal' and 'unlawful' tactics, performance architecture provides for a new political critique of the built landscape. Further, however, it also suggests an implosion of the boundaries of the architectural discipline as we used to know and guard them.

*This text is a modified short version of the essay included in Didier Fiuza Faustino, Salons de l'IFA, Cité de l'Architecture et du Patrimoine, Paris, due for publication in 2012.