In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed The Yosemite Grant, granting Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove to the state of California, the first time that the U.S. Government enacted to protect land for future public enjoyment. This was 13 years after the Mariposa Battalion - with the help of Miwok scouts - entered and obtained the Valley from the two occupying Yosemiti bands, and 26 years before John Muir sparked the founding of Yosemite National Park (at the time, the third national park in U.S. history). For all of known history both written and oral, dating back an estimated 3000 years, people have gazed at the waterfalls, the granite sweeps, the meadows, the streams, the Merced River, and the flora and fauna that make their homes in the seven square miles of creek and river drainage know as the Yosemite Valley.

The Yosemite Valley is small. At seven square miles, it accounts for roughly half of 1% of the total area of the national park (1169 square miles of protected land). Yet, according to the National Park Service, of the 4 million annual visitors, most visit Yosemite for less than a full day, driving the Valley Loop Road and returning to the exit after only a few hours. Overnight visitors average only 2.4 nights' stay, mostly in the Valley campgrounds, Curry tent cabins, housekeeping cabins, and the Ahwahnee Hotel. The most recent statistics gathered by the NPS (2010 year-end stats) show only 53,139 backcountry hikers in the entire park. That's 1.3% of total visitors.

In 2006, after climbing a route on the Book Cliffs one afternoon, I sat on a log near the Lower Yosemite Falls Trail and read a book while thousands of visitors streamed past me. Minus the background and foreground, I could have been looking at a city sidewalk in central Tokyo, Lower Manhattan, or the Thames Path in London. And to my surprise, in two hours, not a single person left the asphalt trail in front of me. I was fewer than fifty feet into the trees, completely alone, and this made me realize that not only do most Yosemite visitors stick to the Valley, but most visitors stick to the paved portions of the Valley, the concessions locations, and the sandy beaches along the banks of the Merced River. This reduces the area of impact even further, squeezing most of the 4 million annual visitors into a square mileage of something less than two square miles. Everyone understands the equation "smaller impact area + heavier use = incredible pressure." Any attending observer can see that. The roads, pathways, parking lots, and beaches are littered with garbage, and even the Curry Village deer herd - maybe the most socialized deer herd in the entire world - hesitates to cross pavement during daylight hours.

On a trip in 2011, I climbed the East Buttress of Middle Cathedral. Sitting on top of The Pedestal before our early morning start, a few hundred feet above the Valley floor, I observed the same phenomenon I always do in Yosemite. Shuttle busses, hikers, cars, bikes, motorcycles, photographers, RVs, horses, and trucks passed below me on the paved trails and roads. No one ventured off the paved trails. And in a way, this is a good thing. People are sticking to the developed areas of the park. They're impacting what has already been impacted. They're not cutting new trails, destroying additional habitats, or dumping hotdog wrappers in the middle of Stoneman Meadow. But all of that human pressure on two square miles is taking its toll. Roads are constantly needing repair, the air quality in the Valley, especially in summer, is poor for a designated wilderness area, and the camping on any dates near July 4th is like camping in a ride-line at Disneyland.

Plus, where the humans congregate, the scavengers scavenge. Coyotes, bears, jays, squirrels, and crows are fattening themselves on human detritus. They're so used to getting food from humans that I once saw a Valley camper throwing rocks at a raccoon to scare him away from his bear box, and that raccoon fielding those rocks like a seasoned third baseman in the Major Leagues. The raccoon deflected the rocks off his chest, picked them up, then tasted each one, knowing that humans generally carry and discard food, good food, good fatty food, and it was worth a few rock bruises to get to the good stuff.

Or take Camp 4 ground squirrels - California Ground Squirrels to be exact. According to biologists, these squirrels should be eating seeds, berries, tubers, leaves, bulbs, or woodplants, and occasionally insects or carrion for added protein. But in Camp 4, I've seen them eating Ramen noodles, marshmallows, candy bars, hamburgers, French fries, toothpaste, and hotdogs, plus puncturing and drinking from soda cans. They'll also steal and eat anything that smells like food. I've seen one devour a greasy foil wrapper as if it were the finest fare in a swanky restaurant.

Visitors complain about the condition of the animals near the campgrounds. I've heard tourists say, "Why is that squirrel so fat" and "Why is that deer's coat so mangy?" Well, the answer is that they're eating what they shouldn't be eating. They're eating our food. They're living a way they shouldn't be living. Their lives are affected by the impact of the laziest visitors, those who drive through, walk a couple of short, paved paths, throw food and garbage to the ground, and drive away. The impact starts with what we can bring into the Valley in our enormous cars, trucks, SUVs, and RVs. With unlimited space in our vehicles, what don't we bring into the Valley? Unfortunately, our garbage bags, our discarded materials, are our legacy to the animals of Yosemite National Park.

For the people who love to visit Yosemite National Park, for the people who love the plants, animals, and scenery, the governmental shutdown of 401 national parks in 2013 was awful. All national parks unavailable for weeks during the gorgeous fall season? That was terrible. Or was it?

Personally, I wanted Yosemite open for all of October. My book publisher (Tyrus Books) had flown me to San Francisco, rented me a car, and I was supposed to do a reading from my new Yosemite novel, Graphic The Valley, in historic Camp 4 on October 5th, at the Big Columbia Boulder under the iconic Midnight Lightning. This location is my own personal Mecca, one of the holiest locations on earth. But the park was closed. All parks were closed. Even if I snuck into Yosemite - an option I considered - there would be no audience at my reading. And as cool as it is to read to myself in the dark, it wouldn't have been the same thing as the originally designed book-release party. My publisher (Ben Leroy) and I hiked into Castle Rock State Park instead, gave away free copies of my books, met climbers, and had fun, but it was no Yosemite. Nothing other than Yosemite is Yosemite.

I felt bad for myself, but not very bad because I felt good for the park. For a few weeks, the pressure on one of the most-visited national parks was lessened. The hordes that invade Yosemite in the fall (and I'm including myself in that statement) were forced to postpone or cancel their sieges. Better than a big vat of boiling oil poured over the wall is a nice, fat, government shutdown. The animals could move freely once again. Air quality improved. And for a few weeks, no one was able to throw garbage out of a car window.

I think a lot about Yosemite National Park. I've camped more than 180 days in the Valley, and researching for my Yosemite novel helped me to discover so much information that I would've never known. For example, from the time of the Mariposa Battalion's entrance to what is now the national park, and their subsequent burning of the natives' acorn stores, westerners have been a huge, negative addition to this wild place. We've brought the railroad, mining, dams, invasive species, illness, buildings, concessions, and unsustainable human numbers. We've damaged this incredible place, this location that was revered and respected for three thousand years by our human predecessors. In only 160 years of westerner use, consider the impact inflicted upon the Valley by the U.S. population and its collective choices.

The problem is clear. But what should we do? Have we gone too far? Have Icarus' wings melted and can we only anticipate an imminent death? Is there any reasonable, saving solution for Yosemite National Park and, particularly, the Valley?

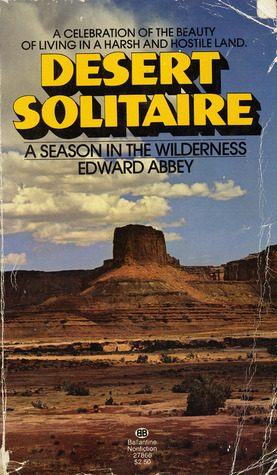

Well, the funny thing is that a logical solution to the Yosemite overuse and heavy impact problem has already been written. 48 years ago to be exact. With his 1968 release of Desert Solitaire, Edward Abbey delineated the clear and intelligent future for the Valley. What should we do to save those seven - or more accurately - two square miles? We should do what Abbey told us to do the year after Yosemite reached 2 million annual visitors in 1967 (with a couple of key modifications that I'll detail later). Abbey's plan, written as "Polemic," is three-fold:

First, no motorized vehicle use in the park. Abbey writes, "Let the people walk. Or ride horses, bicycles, mules, wild pigs - anything - but keep the automobiles and motorcycles and all their motorized relatives out." He goes on to explain that the National Park Service can build large parking lots a few miles outside of the park where people can "emerge from their steaming shells of steal and glass and climb upon horses or bicycles for the final leg of their journey." Why allow people to drive through what was once pristine wilderness? If we don't drive into cathedrals, concert halls, or art museums, why should we be allowed to drive through this great house of worship? Also, "the parks, by the mere elimination of motor traffic, will come to seem far bigger than they are now - there will be more room for more persons, an astonishing expansion of space."

Second, no new roads in national parks. The existing roads are enough. New roads impact flora and fauna, are unnatural and ugly, and cost huge sums of money to clear, grade, and pave. The old roads are good enough for biking and running hourly (quarter-hourly) shuttle busses to haul personal gear, camping equipment, or the elderly. Abbey writes that the saved money from building new roads can be used for trail maintenance and backcountry shelter building.

Third, let the rangers range. Get them out of their booths. Abbey writes, "They've spent too many years selling tickets at toll booths and sitting behind desks filling out charts and tables in the vain effort to appease the mania for statistics that torments the Washington office." If the rangers are out on the trails leading hikes, horseback rides, plant discoveries, animal tracking tours, Junior Ranger programs, and ending the day with fireside talks, they'll be happier, healthier, and more fulfilled. Rangers currently waste a lot of time with car-related actions and infractions (the site of a park ranger directing traffic for an eight-hour shift is always a sad, sad sight), so eliminating cars will go a long way toward improving rangers' work conditions. Eliminating cars will certainly free up the rangers' time. I would add to Abbey's argument here and say that if rangers range with the visitors, mingling in the midst of the crowds rather than staying in booths or directing traffic, fewer Yosemite visitors will throw trash and food to the ground or hand-feed animals. The difference is a middle-school classroom with a teacher present versus a middle-school classroom with a teacher who's left the room for a few minutes.

Under Abbey's initial plan, he intended each family to bike twenty-three miles down into the Valley and twenty-three miles back up out of the Valley, and while this is epic and challenging, it makes visitation of the Valley all but impossible for nearly every U.S. family. The most active families, those with experience road-biking under grueling conditions, with old enough kids to complete 23 miles of uphill riding to the exit, would still be able to visit the Valley from the west, the most used park entrance. But most families would not be able to enter the park from that direction. Thus, I'd like to modify Abbey's plan.

At the Tuolumne and Wawona entrances, visitors could park cars at enormous lots just outside of the park entrances. Concessions possibilities abound right there, boosting local economies. Encourage those concessions, especially in the form of small businesses. Since these will be outside of the park boundaries, the NPS concessions contracts won't apply, and then even the governor of California can get on board with the plan (though he has publicly stated that environmental reform in Yosemite National Park will negatively impact the economy of California). From the Wawona and Tuolumne entrances, visitors could bike, hike, or ride horses into the park. No need to modify Abbey's plan significantly. People could bike to Tenaya Lake in Tuolumne, the dome country and up to Tioga Pass. At Wawona, the south side of the park is accessible from the entrance, with people having a chance to visit the famous groves, historical markers, or even bike up to Glacier Point.

But from the 120 and 140 Road entrances into Yosemite, I suggest regular shuttle bussing for everyone. Visitors could jump on shuttles that would take them all the way into the Valley, all the way to the Merced River drainage. Then, at the western end of the Valley floor, the park visitors could rent bicycles (rentals equaling additional revenue) and bike the remaining distance into camps and concessions areas. This bike ride is a slightly rolling but generally flat ride on good roads through some of the most beautiful scenery in the entire United States. Citizens of all ages are capable of riding bikes through relatively flat terrain, so there is an egalitarian component to this plan. Plus, with the roads free of cars, fatal accidents will be minimized if not eradicated entirely, and the automobile impact on large wildlife will be erased as well. How many cars will hit bears, deer, or elk within the park boundaries if zero cars are allowed to enter the park?

Finally, Abbey writes that children too small to bike will be able to visit the park in the future, but I say let those children ride right now on the shuttle busses. Also the infirm and the physically challenged are welcome on board. It is their right and privilege to visit our national parks as well, and we have to extend the opportunity for enjoyment of our great, wild lands. So anyone who cannot bike may choose to ride the shuttles, hardly a blight upon the land with their regularly scheduled departures and uniform appearances. Hybrid engines with good batteries could lessen their impact even further, and a California plant could build the vehicles in-state for further local revenue.

So with a few small modifications, Abbey's plan is a rational course of action. But there will be significant protest and consternation. Abbey writes that critics will argue "that the majority of Americans would not be willing to emerge from the familiar luxury of their automobiles, even briefly, to try the little-known and problematic advantages of the bicycle, the saddle horse, and the footpath. This might be so; but how can we be sure unless we dare the experiment?" Exactly. Let's give visitors a chance to change. The majority of Yosemite visitors would say that they love the park, so we must let them demonstrate that love through support of environmentally friendly reform.

For a good example of a similar and effective national park plan, consider Zion National Park. In 1997, annual visitation of Zion had reached 2.4 million people per year. The numbers were going up. So the NPS decided to implement a new seasonal shuttle system. From March to November, visitors are not allowed to drive private vehicles on the Zion Canyon Scenic Drive, a section quite similar to the Yosemite Valley Loop Road. The NPS said, "The shuttle system was established to eliminate traffic and parking problems, protect vegetation, and restore tranquility to Zion Canyon." Did it work? Yes. Do some people complain? Yes, again. But visitation has not dropped off. Over the past ten years, Zion's annual visitation numbers have risen to an average of 2.7 million per year. While Zion Canyon has been protected in many ways, people still come. Plus, without private vehicles, the canyon feels more like a national park, even more like a wilderness.

Would this work in Yosemite? Yes. Would visitation be cut in half as some people argue (when referencing significant environmental improvement plans)? Again, if Zion NP is a good example, then no. In Zion, visitation increased after the private cars ban. So visitors will still visit Yosemite as well. Revenue will not be significantly impacted by this proposal. Or what if we modified the proposal even further?

Private vehicles could be excluded from the Valley Loop only. Cars would still be allowed to enter at Wawona and Tuolumne, and even as far as Crane Flats from the West. This would increase the popularity of the lesser-used portions of the park, balancing impact to a significant degree and again minimizing the vehicular onslaught on the Valley. Shuttles could then run from Glacier Point and Crane Flats, down into the Valley, to each campground, natural wonder, and concessioner's point, then back up. If need be, these shuttles could run every 15 minutes to accommodate large numbers.

Since humans generally make things personal, I'll explain what this might look like for a serial visitor to the park: Me.

To be honest, I'm sometimes part of the ugly statistics. Even though I've never stayed fewer than three nights in the park, and I've camped, hiked, and climbed in the high country, I've also driven into the seven square miles of Yosemite Valley and stayed only in that Valley location on nine different visits to Yosemite. So, if "Abbey's Laws" were enacted, or one of my own modified versions, would I still visit Yosemite and would I do things differently?

Well, yes and no. Yes, I would still visit the park, still camp in the Valley and the high country, read under the same trees, make coffee in the beautiful Valley mornings, still swim and hike and climb, and stare at the wildlife and scenery. But I would do things differently too. My mobility would be limited. Instead of driving up the Tioga Road for a day of dome hiking or climbing in Tuolumne, I would stay in the Valley the entire time. I would have to pick between Tuolumne and the Valley on each trip to the park, rather than driving two hours back and forth, getting to do both whenever I wanted. Would this seem like a loss? Maybe. But I'd also feel like a better animal on this planet earth. I wouldn't be wasting gas or putting wear and tear on my car or the park's roads. Also, my family's bikes would see more use than normal. Already our favorite mode of travel in the Valley (an easy way to avoid traffic, travel quickly, and have more fun in the open air) we would now be forced to travel by bike. We would probably also walk further, explore more, and limit trips to the stores to times of absolute necessity. All of these things - when considered fully - are positives. In the new Yosemite Valley, we would live a more local lifestyle, be in better shape, and burn zero fossil fuels. For an active family, there is no drawback to the vehicle ban on the Valley Loop Road.

But what is the economic impact of this proposal? It could be significant. There's no way around that. For a while, it might be as if Yosemite has closed, a second shutdown. The 90%+, those who drive the Loop Road and return to the exit the same day, they will not come. But others will replace those lost visitors. Those who have stayed away because of the driving hordes will now be more interested in the park. If Zion is a model, visitation will still increase, but impact will decrease. Visitors will adapt. They will see the wisdom in protecting the park for future enjoyment, and they will begin to claim that future. The park will be quieter, more peaceful, and more epic. As Abbey noted, seven square miles will seem larger than before. Without individual motorized vehicles, the Valley will lose its Disneyland feel and return as a more wild land.

Plus, consider what it will look like with so many people on bicycles. I run a high school outdoor program in my hometown, and to start the year, we bicycle in a big group for five straight days, visiting different city parks, getting to know the city together on our bikes. Riding with 70 people is managed chaos, but it's fun chaos. We look like a slow-moving biker gang, a smiling, chatting, laughing biker gang. In the new Yosemite Valley, it will look like that: big groups of happy bikers all riding together, or stretched out, cruising through the trees, pedaling and gliding and smiling. And consider the efficiency of bikes as well. According to a 2008 Sierra Magazine article entitled Two-Wheeled Wonder, "Pound for pound, a person riding a bike can go farther on a calorie of food than a gazelle can running, a salmon swimming, or an eagle flying." More efficient than a gazelle, salmon, or eagle? If that doesn't make you want to ride a bicycle, nothing ever will.

And what is the opposite plan, the other option for Yosemite's future? Instead of heading Abbey's advice and implementing his three-part plan (or one of my modified versions), how could we increase visitation and revenue in the park and not make any major changes to infrastructure or rules? I spoke to a regional park planner for the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, and she told me that the NPS planners are under extreme pressure from lobbyists to accept commercial sponsorships of the parks. What would these commercial sponsorships look like if implemented? The parks might follow the National Football League model. We could have Coca Cola Yellowstone National Park. Walmart Glacier National Park. McDonalds Yosemite National Park. Sounds pretty good to me. I don't know about you...

So far planners and park superintendents are fighting these commercial machinations, but the options are worth billions of dollars. Since we are not talking about the U.S. defense industry where individual contracts can exceed 250 billion dollars and therefore a few billion dollars don't matter, the corporate sponsorship money is attractive. According to the Park Service, the 394 national parks generated a total annual revenue of 31 billion dollars in 2010, so additional billions matter in this business, and perhaps that is the problem: the major national parks are big business in the United States. Those who hope for future wilderness areas - and not developed outdoor businesses - are rooting for the planners to hold their ground. But will they?

When it comes to Yosemite alone, do we want more human pressure on the Valley? Do we want extended concessioners' influences? Do we want to see a Golden Arches next to the LeConte Memorial? Maybe a Motel 6 at Yosemite Village? Or a 7-Eleven in the Mariposa Grove? And is it far-fetched to imagine that we could double the park's visitation numbers once again, as we did in 1954, 1967, and 1996 (the year the park first reached 4 million annual visitors)? What would Yosemite Valley look like on July 4th, during a year in which the park experiences 8 million annual visitors? Is that what we want for the future of one of our greatest protected wilderness areas?

Like cell phone and computer proliferation, suburban development, genetically modified food, and outsourcing of U.S. labor to the East, we have to either say, "Enough," and stop or slow down, or we can choose to keep throwing items into the great pressure cooker, keep packing them in, and turning up the heat once again. Because pressure cookers never explode, right?