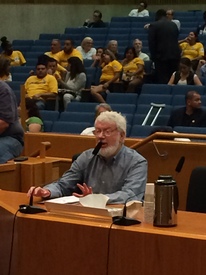

Low-wage workers and community activists rally on Tuesday in favor of a $15 minimum wage law in Los Angeles County, cheered on by Supervisors Sheila Kuehl (in yellow jacket), Hilda Solis (green jacket), and Mark Ridley-Thomas (blue suit)

Three years ago residents of Altadena, an unincorporated suburb (population: 43,000) near Los Angeles, engaged in a bitter battle over whether to allow Walmart to open a store. The nation's largest private employer was the topic of much controversy in part because it is infamous for paying poverty wages to most of its employees, many of whom have to work at a second job and utilize food stamps and other government subsidies in order to make ends meet. But starting next year, the Altadena Walmart, which opened in March 2013, will be paying all of its employees at least $10.50 an hour and will be paying $15 an hour by 2020.

If you think that the Waltons -- the heirs to Walmart founder Sam Walton who control the company and are among the wealthiest families in America -- suddenly developed a social conscience, think again. Walmart and other Altadena employers will be paying higher wages because on Tuesday the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors adopted a minimum wage that applies to employers in the County's unincorporated areas, which are not part of local municipalities and depend on the County for police, fire, library, and other services.

The vote came on the heels of a similar plan adopted by the City of Los Angeles in June. Together, the city and county laws cover about half of the nearly 5 million workers in sprawling Los Angeles County, the nation's largest county.

After it goes to $10.50 next year, the County plan will raise the pay floor to $12/hour in 2017, $13.25 in 2018, $14.25 in 2019, and $15/hour in 2020, and then increase each year indexed to the Consumer Price Index. (Small businesses will have an extra year to reach the $15/hour level.)

The minimum wage victory is the result of a dramatic change in the make-up of the Board of Supervisors, a five member panel that is one of the most powerful and invisible governing bodies in the country. Last year, voters catapulted Democrats Sheila Kuehl and Hilda Solis into office, where they joined incumbent and fellow progressive Mark Ridley-Thomas to form a 3 to 2 majority. Both are political veterans who replaced more moderate Democrats who left the board due to term limits. Kuehl, the first openly gay member of the state legislature, served six years in the state Assembly and eight years in the state Senate, where she led battles for paid family leave, universal health insurance and anti-discrimination laws. Solis, a former Congresswoman, served as Secretary of Labor during President Obama's first term.

Kuehl sponsored the minimum wage ordinance and, as expected, enlisted Solis and Ridley-Thomas' support. Republican Supervisors Don Knabe and Michael Antonovich voted against the ordinance.

"As the nation's largest low-wage region, LA's economy stands to gain billions of dollars and lift hundreds of thousands out of working poverty," said Kuehl after the vote. "This is an historic win against growing inequality in the richest county in the richest country on earth."

Los Angeles County has more poor people (about one-fifth of its residents) and more millionaires than any county in the nation.

About one-tenth of the county's 10 million residents live in unincorporated areas. Approximately 390,000 workers are employed in parts of the county falling outside the 88 incorporated cities.

The current minimum wage in California is $9 an hour, which will increase to $10 next year. The federal minimum wage has been stuck at $7.25 since 2009 because of Republican opposition in Congress to any increase. Studies show that the typical minimum wage worker is in his or her late 20s and early 30s and supporting a family, not a teenager working for pin money.

A $15 an hour wage translates into an annual pay of $31,200 for full-time, year-round workers. According to a just-released United Way report, a family in Los Angeles County with two adults and two children needs to earn $59,919 a year to make ends meet. Thirty-seven percent of families in the county make less than that amount.

Attention will now shift to the other 87 incorporated cities in the county, whose employers may find it harder to attract workers if employers in LA and the unincorporated areas are paying a few dollars more an hour. Coalitions of religious, community, civic, nonprofit, and labor groups in Long Beach, Santa Monica, West Hollywood and Pasadena are already working to persuade their local city councils to adopt a similar plan.

Close to 800 people packed the auditorium at the county's Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration building in downtown LA on Tuesday. A number of business owners and representatives of about a dozen Chambers of Commerce from across the county showed up to voice their opposition to the pay hike, but the overwhelming majority in the audience came to support Kuehl's minimum wage proposal.

Many of them were low-wage workers -- janitors, hotel housekeepers, clerks in big-box stores like Walmart, home health care aides, and others. Quite a few carried signs saying "Fight for $15" and wore tee-shirts emblazoned with the same slogan. Many were mobilized by UNITE HERE, SEIU, and the United Food and Commercial Workers unions and by activist community groups like LA Voice, the LA Alliance for a New Economy, and the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE).

"I go to school full-time, and I work full-time, so if we were to get paid more, I'd focus more on school and less on my job," said Roberto Balanzar, who attends Long Beach City College and also works at Burger King to help support his mother (who also works in food service) and four younger brothers. "My mom's getting help from the government. That's something I don't want my mom to do. Or me. I don't want that in the future. I want to work for my own stuff." He hopes to transfer to a four-year university to study engineering.

Nancy Berlin, policy director for the California Association of Nonprofits, testified that 77 percent of her group's members -- many of whom serve low-income people -- support the plan to raise the minimum wage. "We don't want to create a low-wage workforce among nonprofits," she said. "It creates high turnover and a lot of disgruntled people who are trying to do good work in the community."

Balanzar and Berlin were two of about 175 individuals who signed cards requesting to speak at the marathon hearing, which lasted from 11:20 a.m. to 2:45 p.m. Rather than invite them to speak on a first-come, first-serve basis, Antonovich -- who chaired the meeting because he is the County's "mayor," a rotating position -- allowed elected officials (including LA Mayor Eric Garcetti, LA City Council member Marqueece Harris-Dawson, and West Hollywood Mayor Lindsey Horvath) to speak first. After that, Antonovich gave preference to the opponents of Kuehl's plan, including representatives of various business lobby groups, although he sprinkled a few proponents among the early speakers to avoid looking completely one-sided.

Antonovich no doubt knew that by putting the opponents at the front of the line, many of the advocates in the crowd -- especially the low-wage workers who took time off from their jobs to attend the meeting to tell their stories about the difficulties living on poverty wages or just to support the cause -- would have to leave before the Supervisors voted, depriving them of an opportunity to celebrate and feel part of a history-making moment.

Thanks to Antonovich, I was the last speaker, addressing the Supervisors right before they took their historic vote. Antonovich clearly intended this to be my punishment for an article I wrote two weeks ago in the Huffington Post attacking him for hiring, at a cost of $55,000 of taxpayers' money, a restaurant-industry front group called the Employment Policies Institute (EPI) to write a report evaluating the impact of adopting a county minimum wage.

The author testifying at the county minimum wage hearing and (right) with Supervisor Michael Antonovich in the background presiding over the meeting.

As I wrote in that piece, "Hardly anyone takes EPI seriously as a source of impartial information. Asking EPI to do a 'study' of the minimum wage is like asking the National Rifle Association to look into the advantages of gun control or hiring Donald Trump to examine the pros and cons of Mexican immigration."

I noted that EPI has been the subject of widely-publicized investigations and exposes by the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe, USA Today, CBS' 60 Minutes, CNN, and others. "There's no way that Antonovich could be unaware of EPI's role as a corporate front group and its reputation for distorting the truth," I wrote.

Understandably, Antonovich was not pleased with my article. So he took his revenge by making sure that I had to wait almost three and a half hours before being allowed to make my one-minute presentation, even though I was among the first people to sign up to speak.

I didn't mind waiting to speak, because I was inspired by the many low-wage workers who demonstrated great courage in testifying publicly about the hardships they faced in making ends meet and the abuses they encountered from employers when they sought to organize.

But I found it both amusing and disconcerting that Antonovich, who has served on the powerful Board of Supervisors for 35 years, and who will be leaving office next year because of term limits, would engage in such mean-spirited and petty tactics.

Antonovich may be vindictive and spiteful, but he can count votes. Long before the meeting even began, he knew that he was going to lose the minimum wage battle by a 3 to 2 vote.

The flawed and biased report that EPI provided the Board of Supervisors didn't change anyone's mind. Nor did Antonovich's last-ditch effort, before the supervisors cast their votes, to make the case against the wage hike by echoing the Chamber of Commerce's worn-out talking points that they've been using since California Governor Hiram Johnson successfully advocated a state minimum wage in 1913 and President Franklin Roosevelt introduced a federal version in 1938. It will, according to the conservative mantra, "kill jobs." It will force businesses to shut down or move. It violates the spirit of "free enterprise." It was meant to be a starting salary, not a "living wage." Workers who work for tips -- such as waiters, waitresses and car washers -- don't need the higher minimum wage.

Business lobbyists and their political allies have been spouting these sentiments for decades -- as a report by the National Employment Law Project and the Cry Wolf Project documents -- even though there's no empirical evidence to support them. But that didn't stop Antonovich -- as well as the Chamber of Commerce executives from Los Angeles, Santa Clarita, Glendora, Monrovia, Torrance, Altadena, East Los Angeles and other parts of the county -- from warning about the pending catastrophe, just like the boy who cried wolf.

In addition to adopting a minimum wage for employees in unincorporated parts of the county, the Supervisors also voted to adopt the same policy for LA County's own 100,000 employees. They also added a provision to help guarantee that the law is enforced by creating an initiative to monitor and prosecute "wage theft" by employers that fail to pay workers their full salaries. The Supervisors also expanded the existing "living wage" for employees of firms that have contracts with the County for custodial, gardening, food service and other services. Those contractors will have to pay workers $15.79 an hour by 2018.

The new minimum wage in both LA County and the City of Los Angeles is part of a growing movement among low-wage workers and their allies around the country to increase their pay by pushing state and local government policymakers to raise minimum wages and by putting direct pressure on employers to hike pay rates. Over the past few years, employees at fast-food chains, Walmart, and other corporations have engaged in rallies, protest marches, and even civil disobedience to press their cause.

In response, an increasing number of cities, including Seattle, San Francisco, Oakland, Kansas City, and Chicago, have adopted mandated wage hikes and dozens of other municipalities are thinking of doing likewise. New York State is expected to soon adopt a $15 an hour minimum wage for fast-food workers.

The movement has shifted public opinion, too. A recent poll by Hart Research Associates found that 75 percent of Americans (including 53 percent of Republicans) support an increase in the federal minimum wage to $12.50 an hour by 2020. Sixty-three percent of Americans support an even greater increase in the minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2020.

Kuehl compared the growing movement for living wages to the first women's suffrage gathering in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848, the first lunch counter sit-ins in 1960 in North Carolina that challenged segregation laws, and the 1969 protest at the Stonewall Bar in New York City that triggered the gay rights movement.

"At different points in our history, people drew the line and said things have to change," Kuehl said. "Today is one of those moments."

--

Peter Dreier is professor of politics and chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College.