Nostalgia still ain't what it used to be. But what is it now? A marketing ploy that makes us long for the past because we're supposed to long for the past? A post-modernist trope that would have us disdain the past by admiring it? An FX miracle that would make us think we're in the past even as we witness its simulacrum? Well, photography and painting, soooo last century, are hardly the most complicit media in this manipulation, but they are arguably the most effective, as they speak with either the authority of relics - they are the past - or with their makers' solitary immediacy, manifesting their nostalgia, and just maybe yours.

Richard C. Miller has been wielding a camera since before World War II, and his archives (selected as "Over the Long Run" at the Craig Krull Gallery until April 17, www.craigkrulllgallery.com) now documents faces and facets of Los Angeles that are long out of reach to us. But Miller's images still ring with familiarity; after all, they document one of the world's most photogenic places, a city that began acting as a backdrop for cinematic imagination well before even Miller came along.

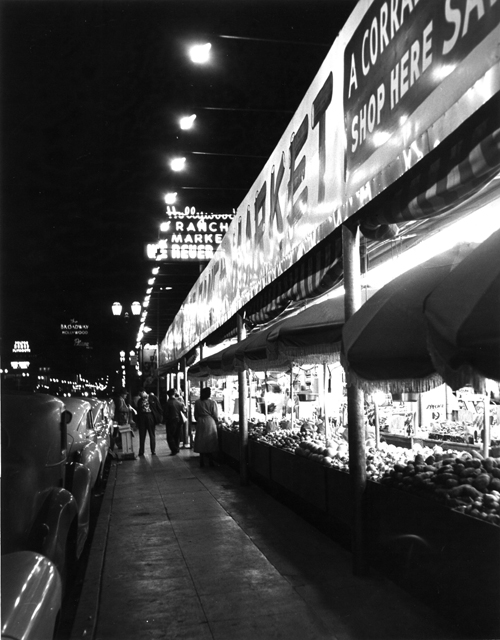

RICHARD C. MILLER, Hollywood Ranch Market, 1949, Gelatin silver print, 8 x 10 inches

The views and faces he captured were captured by others, and were infinitely capturable. Beyond their technical curiosity (the painterliness of his color, the angles he achieved on certain outdoor shots), Miller's photos jar for their very familiarity, or their near-familiarity. Norma Jean Daugherty's face launched a thousand ships, but Miller's image of the future Marilyn Monroe as a Bible-bearing bride is at once hilariously incongruous to our eyes and still lovely, her pre-bobbed nose gracing that generous face. Miller's other magazine pix (including endearing set-ups featuring his daughter) conjure Norman Rockwell avant la lettre and his conventional shots (nudes, portraits) are more than competent, but it is his black-and-white documentaries, one of the Weston family at their zenith and one of the Hollywood Freeway a-building, that earn Miller a place not just in the LA Historical Society, but in LACMA.

RICHARD C. MILLER, 4 Level #8, 1949, Archival silver print, 56 x 43 inches

The latter sequence, especially, establishes Miller as the Julius Shulman of the highway, recording the breadth of the changing LA landscape the way Shulman recorded its depth.

Miller, still active toward the century mark like his recently deceased contemporary, has produced a stunning body of artwork almost by accident; his most memorable images were done for commercial or organizational clients. Irony is not in his vocabulary; but it is in ours. In our awareness of the irretrievability of such periods, or even moments, we know that the golden glow that suffuses our regard for them comes from our sense of absolute loss. You can't go home again. In her new work (at Rosamund Felsen until April 17, www.rosamundfelsen.com) Karen Carson even seems to mock the human tendency to nostalgia, giving its dreamlike quality a nightmarish tint. Setting dancing figures - dancing in all manners, from ballroom to ballet to American Bandstand - inside strange, smeary landscape spaces, unspecific except for the spectacular, even apocalyptic explosions that silhouette (and sometimes surround) the dancers, Carson imbues her pictures with a frightening energy. But it frightens less because of those bombs and fireworks than because of the figures doing all those familiar turns - and because of the music(s) their dance steps suggest, music that lives in our heads, that keep insisting we can go home again.

Canadian painter Kim Dorland titles his show (at Mark Moore until April 17, www.markmooregallery.com) "1991," and you get why almost as soon as you lay eyes on the paintings. Thickly and goopily rendered with sometimes violent slashes, but openly and lucidly composed, Dorland has created a procession of images that record moments from his (or someone's) adolescence, moments of crashing banality and/or teen angst whose very vacuity allows Dorland's technical virtuosity to proceed unimpeded by the need to tell much of any story. Just enough story emerges, in fact, to sour us on the very idea of nostalgia; Dorland embarrasses us with the recognizability of his dopey subject matter.

But if "1991" makes a deliberately silly construct of the nostalgic impulse, "1962" makes it ominous. Lawrence Gipe's paintings, showing under that calendar rubric (at Lora Schlesinger until May 15, www.loraschlesinger.com) recapitulate images from the year he was born, placing them post-Miller, pre-Dorland, burnishing boomer memories of Them that come with the duck-and-cover fear that pervades Carson's nightmares. But 1962 was a strange year, a year of showdown with an enemy who was at the same time showing us a less implacable, more human face, a year when Khruschev signaled that the USSR wanted to be contained. All of Gipe's images are taken from Soviet propaganda publications, meant both for local and for international consumption and thus meant to project military might and social paradise, responsibility for the world and Russian-homeland patriotism.

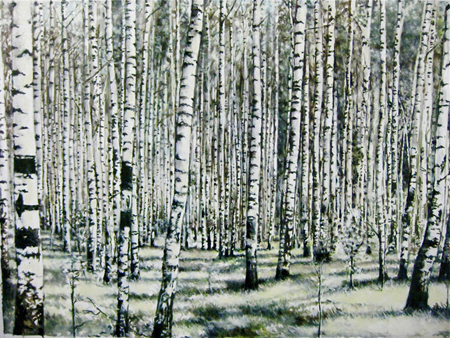

LAWRENCE GIPE, No. 4 from 1962 (Birches), 2010, Oil on canvas, 37 x 50 1/2 inches

The images seem at first innocuous, particularly as Gipe composes them and renders them in a near-grisaille highlighted with the lurid color of 1962 Soviet printing. They rumble with emptiness, their saber-rattling and their cinematic romanticism now apparently rendered as meaningless to us as Napoleonic history painting. But by reformulating these pictures of the past as history paintings, Gipe avers that the bygone eras of our lives are never quite gone, not from our shared, public lives and not from our personal recollections. While we cannot go home again, we are always going home - circling back on what we remember, and how we remember it.

LAWRENCE GIPE, No. 5 from 1962 (Warsaw), 2010, Oil on canvas, 37 x 50 1/2 inches

NB: All these galleries are located in Bergamot Station, 2525 Michigan Avenue in Santa Monica.