We talk urgently about what's in the galleries, but the not-so-dirty little secret is that, no matter how dynamic, progressive, and ambitious an art scene is, its heartbeat and its intellect do not reside first and foremost in its commercial outlets. Not in America's cities, certainly. There's plenty of interesting stuff in the galleries, to be sure; they remain the best places to see bodies of recent work by many contemporary artists, and a few of them, at least, propose thematic essays of reasonable substance. (How's that for faint praise?) But, certainly these days, galleries are only as adventurous as they can afford to be; they are businesses, after all, businesses that cater to a limited clientele, and that clientele dictates the tenor of the galleries more than any other single factor except perhaps the taste(s) of the gallerists themselves. The liveliest galleries, arguably, are the small artist-run outlets where making a statement comes before making a living, which is why galleries in Chinatown, the Lower East Side, and the Mission District (insert your Chicago, Houston, and Miami neighborhoods here) are more "fun" than those in Culver City, West Chelsea, or Union Square - and why those in Highland Park, Bushwick, and Oakland are funner still.

Los Angeles has never really been a gallery-driven scene. Its non-commercial spaces, from large museums to school exhibition spaces to municipal galleries to various non-profit organizations, have always played an outsize role in the discourse of art. Sometimes that role is more prominent than at others, and the burgeoning multi-neighborhood gallery scene of the last 20 years has seen the public sector through an extended lean time. But, no matter how fund-starved (and/or mismanaged) the non-commercial spaces may have been, they have persevered - especially at the fringes of the LA metro area, where an archipelago of smaller-size exhibit halls has fed a hunger for visual art that simply doesn't sustain at the commercial level. In LA, commercial galleries cluster, but non-commercial galleries scatter.

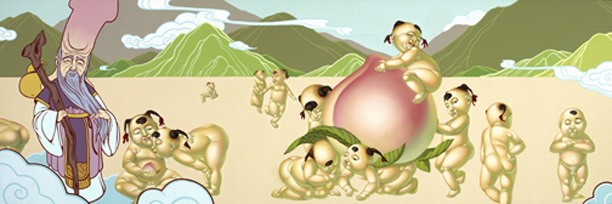

Pasadena's Armory Center for the Arts is a case in point - although Pasadena itself, brimming with museums, artists and collectors, is hardly an art-starved outpost. The Armory Center's community-oriented programming is closer to the ground than, say, the Norton Simon Museum, but it casts its net broadly. Shows there balance contemporary themes and contemporary individuals. Among recent exhibitions, "Stitches" aggregated the work of a dozen artists hailing from across the globe, and no less various in their styles and media. What united their approaches was their reliance on sewing, knitting, and weaving, a reliance that makes itself powerfully felt in all their work. Thus, Nuttaphol Ma's woven plastic-bag installation, Nicola Vruwink's crocheted cassette tape objects, Dinh Q. Le's interstitched photographs, Ruby Osorio's paper-and-embroidery images, and the hand-stitched canvases of Elias Sime all appeared nothing like one another, but felt almost of a piece, their formal logic and roughly sensual textures determining a sensibility that at once embraces and transcends craft. By contrast, "Ascending Dragon: Contemporary Vietnamese Artists" found a notable diversity among compatriots. Some of the six artists still live in Vietnam and some now live here, but their genius lies in more than just their loci; they were selected for their breadth of imagery and ready recourse to the eccentric treatment of material and image alike. From cartoons to salt crystals, these emergent artists speak less from experience they share with one another than experience they share with a divergent audience.

NUTTAPHOL MA, Piano Lesson, Tchaikovsky's Cocoon, 2010, Mixed media, 100 x 72 inches

NICOLA VRUWINK, pop rocks, moonlight skate, a&w teen burgers, keds.... track meets, cassette tapes, 2010, 2010, Crocheted cassette tapes, speakers, audio wire, Courtesy of the artist and d.e.n.contemporary, West Hollywood

PHUNG HUYNH, Live Long and Prosper, 2009, Acrylic & oil on canvas, 24" x 72"

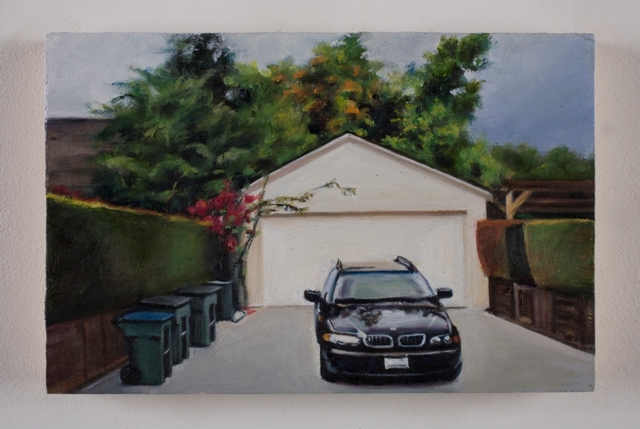

Note should be made also of the intimate but virtuosic installation of very, very small paintings by Elizabeth Saveri, whose "The Trees on My Block" examines her neighborhood through - and on - its plant life, and of Quinton Bemiller's own colorful recapitulation of local vegetation, Hahamonga, installed in and on and around the Armory Center's central staircase.

ELIZABETH SAVERI, Robin and Kaz's Eugenia, Bougainvillea, Chinese Elm, Grevillea Robusta and Pecan Tree, 2010, Water-based oil on wood, 5 x 7 1/2 inches

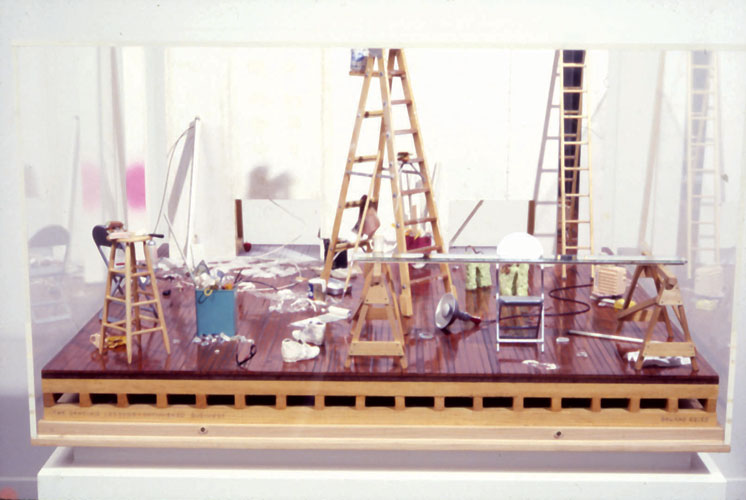

The Torrance Art Museum, hovering in that desiccated prairie between metro LA and the harbor, is actually a Kunsthalle (to use the German term for an exhibition hall without its own collection - although doubtless, someone from Torrance is likely to write and tell me that, indeed, they have a collection). It is also one of the sprightliest art spots in the Southland. The Museum has launched a series of shows called "Set Theory," each built around a "nexus-point artist" deemed central to local dialogue and practice. Roland Reiss, the man who put Claremont's graduate art program together and on the map, made a logical inaugural nexus-pointer; "Set Theory 1" arrayed the work of various artists he taught or otherwise influenced around work of his own from several points in his long career. Over that career Reiss has oscillated between representation and pure (and not-so-pure) abstraction; here, several dollhouse-like "story boxes" from the 1970s and '80s were augmented with a couple of recent paintings, including one of his latest - of a bouquet.

ROLAND REISS, The Dancing Lessons: Unfinished Business

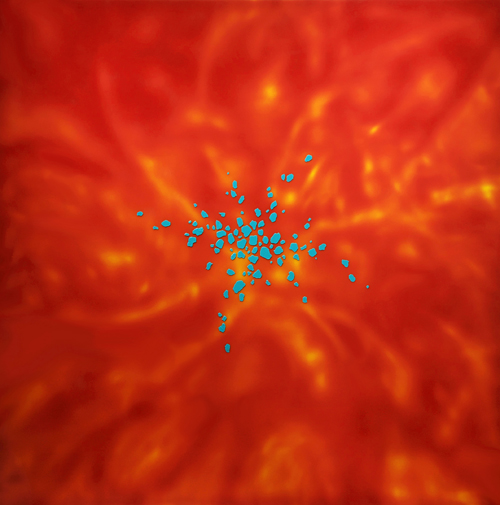

JASON EOFF, Eyebeaters

Between them hung and stood a variety of paintings and sculptures, most of which tended to the abstractly, intensely colorful. (Claremont was a locus - nexus? - for the "return-to-beauty" abstract painting of the '90s.) Given Reiss' vast network of colleagues and ex-students - and the often-surprising shifts in his own oeuvre - the stylistic range could have been rather broader, but with artists such as Jacci den Hartog, Dion Johnson, Lisa Adams and Jason Eoff included, the selection did have an edge to it. So did the show of Briton Susan Collis next door, an installation that emptied the room of all but a few screws in the wall - screws fabricated, with disconcerting and hilarious verisimilitude, from "exotic materials," including precious metals and even gemstones.

Tromping l'oeil is also the modus operandi of Argentine installationist Leandro Erlich, whose Lost Garden graced the back gallery of Long Beach's Museum of Latin American Art - one of the newest and most compelling of the LA area's public art spaces. Erlich came to some attention nationally with his ersatz swimming pool installed in the dead of this past winter at P.S.1 in New York. Perhaps it would have been a bit more, er, appropriate to have shown that walk-under structure in endless-summer LA, but MOLAA's handsome new galleries allowed only for a more conventional structure, a fern-strewn garden planted within windowed brick walls. Visitors could look in but not step in - and when they looked in, they saw themselves reflected, at extremely unlikely angles, in what seemed to be the windows on the opposite wall. Ah, but there was no opposite wall in the triangular construction; Erlich, a first-order, almost Escherian trickster, deftly confounds perceptual expectations in his pieces without defying physical, or even optical, logic.

LEANDRO ERLICH, view of Lost Garden

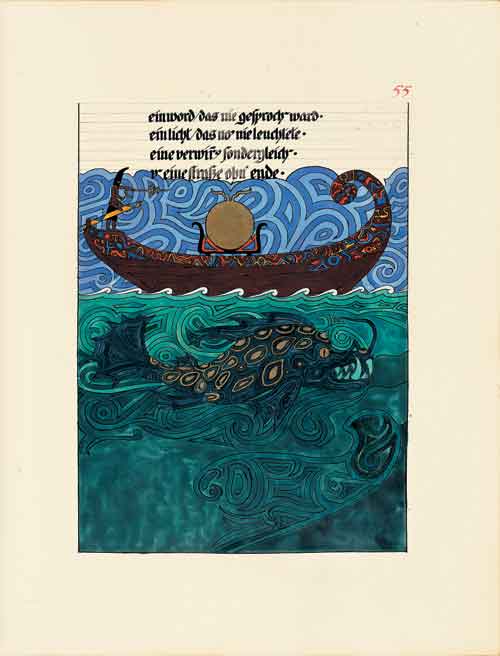

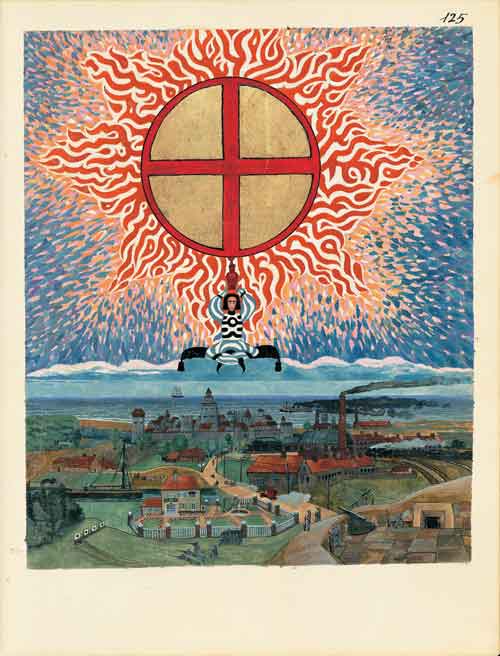

If Los Angeles' art community has a "favorite public space," it is the right-in-the-middle-of-town Hammer Museum, situated at the front of bustling Westwood Village and administered by nearby UCLA. Run for the past decade as a blend of laboratory, archive, and showcase (appropriate to a university museum, but, as it happens, also echoing the larger ambitions of the nearby Getty Center). At any given time you can find the Hammer's nether spaces filled with contemporary artists' projects, some of which can impinge upon its notable (if just short of world-class) permanent collection. What prompted my latest visit, however, was the display of a century-old project, Carl Gustav Jung's Red Book. Recently published in full-scale facsimile by W. W. Norton & Co., the original volume and related paintings and drawings were first shown at the Rubin Museum in New York, then sent out this way to boggle more minds. Begun by the Swiss psychoanalyst on the eve of middle age - and the First World War - the immense scrapbook is filled with mandalas, creature fantasies, elaborate color designs, and other conjurations that self-consciously but sensitively marry the visual traditions (religious and otherwise) of West with East in the exploration - revelation, really - of their shared forms and motifs. Jung's hand was remarkably able, but more significantly, his entire approach reveals itself as profoundly aesthetic, not just in result but in intent: he clearly read the world as art. In this respect, he mirrored the synthesist mindset of other thinkers of his time and place, from Paul Klee to Rudolf Steiner. Indeed, to judge from The Red Book, Jung thought more as they did than as Freud did.

CARL G. JUNG, from the Red Book, 1913-1930