The year is 1990. The time is 4 a.m. The place: Princeton. I am jolted awake by ambulances with sirens screaming, police cars, a trauma helicopter circling overhead. I live near the train station. I peer through the window at a cluster of flashing lights converging in the snowy night

Not until the next day did I find out what had happened. A group of college sophomores, after partying all night, decided to fool around. they climbed on top of the little train, nicknamed the Dinky, which shuttles people into Princeton from the main station, about five minutes from campus. The student who was first to get on top of the roof was wearing wearing a metal watch on his left wrist. Eleven thousand volts of electric current surged through the watch into his body. Eleven thousand volts! That number I never forgot. Now he was dying.

In the weeks that followed extra security measures were put in around the Dinky. Then I moved back to Holland and I heard nothing more about the incident. But memories of that gruesome night always stayed with me. I often wondered about the poor student who had paid such a high price for a single moment of youthful indiscretion.

Then I recently read an interview with the title "A Shock" that led to insight. When reading the first line, my heart almost stopped: "We all have a reason to wake up in this world. For me it required eleven thousand volts."

To my surprise, 25 years later, I had found BJ Miller, the hapless student. He had not died. On the contrary. In the accompanying photo was a lively, handsome, newly married man in his mid-forties. That unfortunate night had cost him three limbs, but he had not let it sidetrack him. "I decided I did not have to 'overcome' my situation but rather to play with it and be fed by it." Less than two years later he played in the U.S. Open volleyball team in the Paralympic Games in Barcelona.

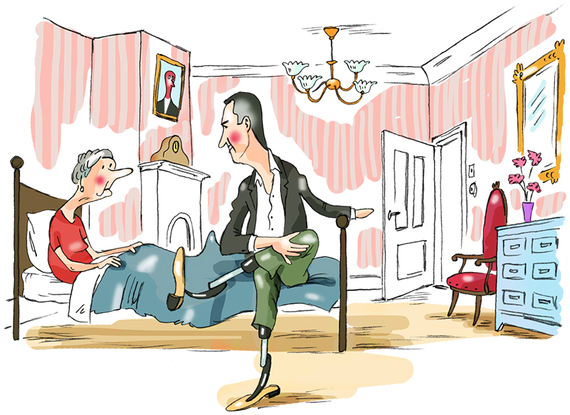

He changed his academic studies to art history, since art offered him consolation. "Artists give shape to what it means to be human, with all its blackness." His study of the Chicago school of architecture, changed his attitude about his prosthetics. At first he had covered them with pieces of foam and socks, but then he dropped all of pretense and let the prosthetics speak for themselves -- just as unadorned structure of a building reveals its true nature.He returned to graduate from Princeton with his original classmates and went on to medical school.

BJ Miller is now director of the Zen Hospice in San Francisco. A place where people prepare to die on their own terms. Since he had looked death in the eyes, it changed the way he looked at life. "I'm not afraid of death," he says. "I'm more afraid of not living a full life. It is important to live so that you're preparing for a good death."

He feels most at home among people in the last and most vulnerable stage of their lives. In his own words: "Every day I feel I have a head start when I meet patients and their families, because they know I've been in that bed. That can take us to a much more trusting place more quickly."

He finds it a challenge to guide them, as best as he can, toward the things that matter: smell, touch, food, art, love, friendship.

Eleven thousand volts jolted BJ Miller to life.