I rang Debra Brown just as she wrapped up her shift making ice cream sandwiches at a factory in Richmond, Utah.

Last we'd spoken, Deb had started telling me about the day her kids visited her for the first time at Utah State Prison, where she was serving a life sentence for murder. The visit had gone for an hour, but flew by so quickly it felt like 10 minutes.

"You're just starting to numb up to being in prison and then you get to be around these precious ones that you love so much, so when they leave you hit bottom again," she'd told me. "You just have to wonder if it was even worth it."

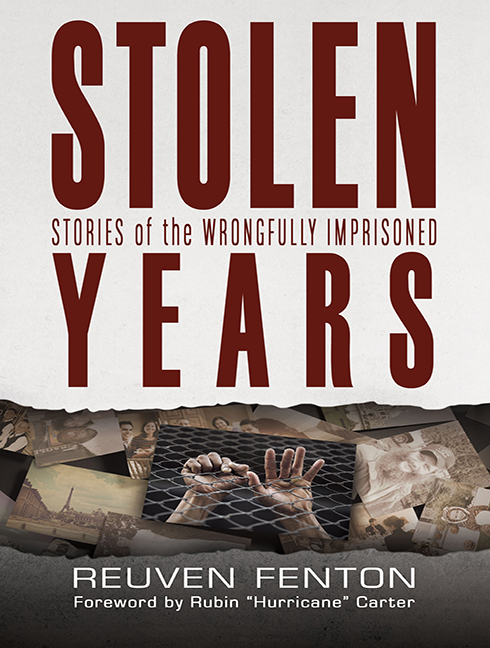

Now, on the phone, Deb sounded tense. I asked if now was a good time to continue her story -- one of 10 that would comprise my book, Stolen Years: Stories of the Wrongfully Imprisoned.

"Sure, we can talk," she said. Then, after a beat: "You know, Reuven, ever since we've started talking, I've been having nightmares again."

I took a deep breath. "Sorry, Deb," I said.

"It's OK. I knew going into this that it wasn't going to be easy. But Jensie (my lawyer) said this was important, which makes it important to me, too."

And we eased back into her awful tale, and as Deb got into it her voice settled and became girlish again. She even chuckled once or twice. And I took it all down.

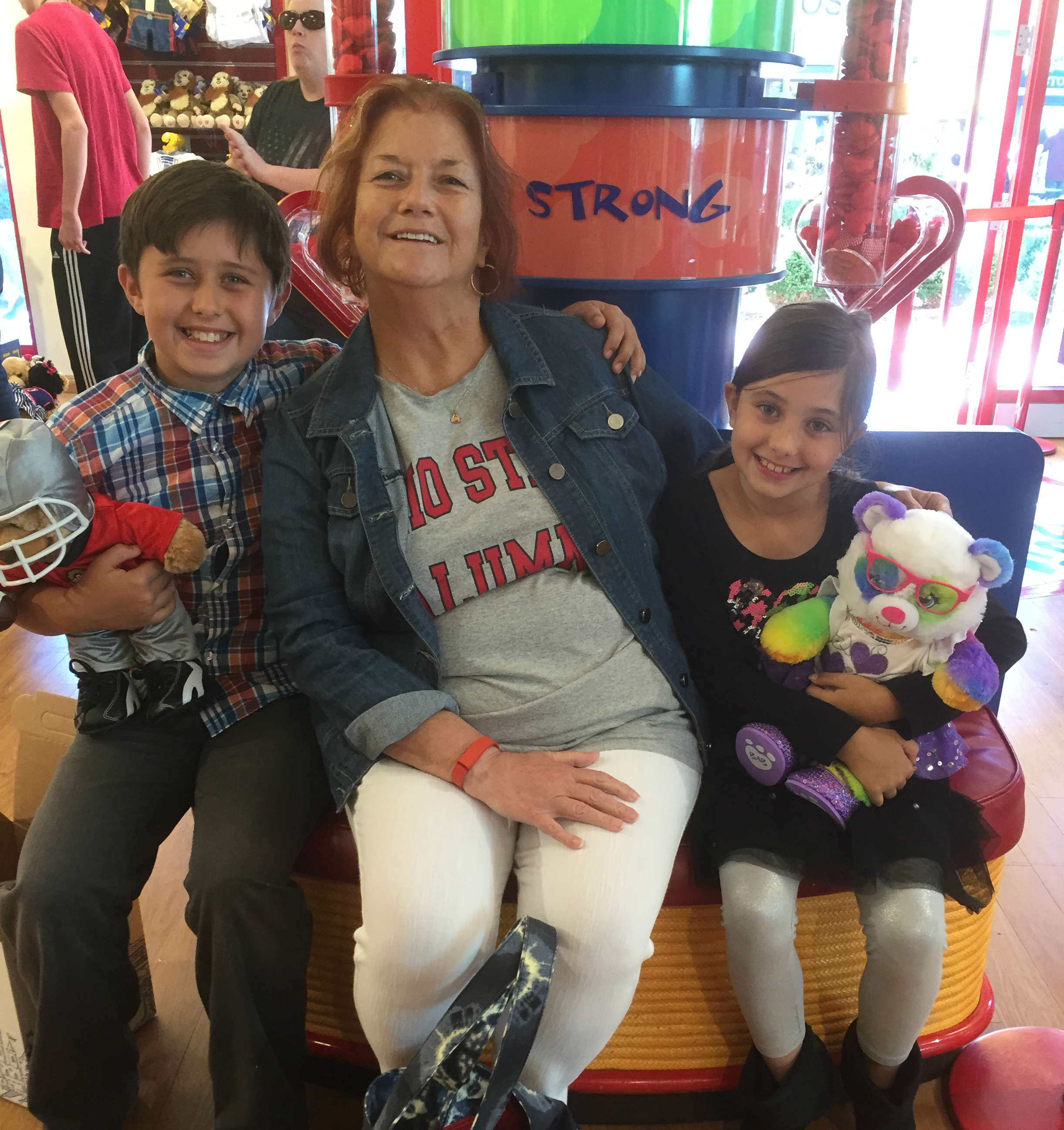

Deb Brown

Deb Brown

I peppered Deb with questions for some dozen hours over the course of several weeks. Her story needed to be told. But the emotional toll it took on her was dear.

And now the burden is on me to make it up to her.

When people talk about their worst nightmare, it tends to be about something so terrible that the odds of it happening are almost zero.

A frequent flyer's worst nightmare is a plane crash. A mother's is having her child whisked away by a stranger at the park the moment she looks away.

As a New York City newspaper reporter, I cover worst nightmares for a living.

This year alone, I interviewed a man who buried seven of his eight children after a malfunctioning hot plate caused his house to burn down. I talked to a young man whose father, hours earlier, was shoved onto subway tracks just before a train barreled into the station. I interviewed a woman whose brother executed two New York City police officers and then killed himself.

Not too long ago, I got an idea for a book that would focus on a particular nightmare that has always haunted me -- the one about people who go to prison for crimes they didn't commit.

It was always that randomness, that improbability, that got to me. The idea that you're the one-in-a-million guy who's inadvertently plucked off the street and thrown into jail, and the next thing you know you're on trial for murder. And when you keep telling people you're innocent, all you get in reply is, "Yeah, we hear that a lot."

And so I started interviewing some people this happened to -- a handyman in Chicago, a barber in Philly, a bricklayer in Louisville, a deckhand in New Orleans -- who scarcely knew what hit them until the day they were asked to stand for their sentence.

At that moment, each assumed he or she would be found innocent, because a guilty verdict was just too ridiculous to fathom. It would be the stuff of horror movies. Fiction.

Then the jury foreman said, "Guilty."

When asked what that guilty moment was like, Ginny LeFever of Ohio, who did 21 years for murdering her husband, said, "I felt instantly like my heart had been packed in a container of ice, and there was ice in my veins."

Ginny LeFever

Ginny LeFever

Devon Ayers of New York, who did 17 years for murder, said, "I'm wondering, how did I get to this stage in my life? That's the first question you ask after you snap back to reality. How did I get here? How did this happen?"

And Deb Brown, 18 years, said, "It's like everything goes fuzzy. You can't believe what your ears are telling you. The unthinkable. The unimaginable. The thing you knew just was not gonna happen happened, and there wasn't a thing I could do about it."

The thing you knew just was not gonna happen happened...

But I discovered something surprising after I began researching this book: Wrongful convictions aren't that unimaginable. Some studies have found as high as five percent of prison inmates are innocent.

What made my 10 subjects' stories so unique was that they actually got freed.

As of writing this, the National Registry of Exonerations has listed 1,689 people who've been freed after wrongful convictions listed since 1989. That relatively tiny number reflects the enormous obstacles that stand in the way of exonerating a wrongfully convicted person. Finding a lawyer to take your case, convincing a judge to hear your case, collecting enough years-old evidence to built reasonable doubt are just some of the mountains you must climb.

Most wrongfully convicted inmates don't even make it to the first step. They serve out their sentences to the end -- which, for many, is death.

For those lucky enough to make it out, the stories are anticlimactic. Deb Brown was dumped back into civilization as unceremoniously as when she was taken away. She won a financial settlement with the state of Utah following her release, but not for enough to retire on. Her relationships with her three children and brother are strained and awkward. The world she once knew has completely changed.

And here I come, out of nowhere, asking her to revisit a trauma she's been trying to keep buried.

Over the nine-month period it took to research and write Stolen Years, I put my heart and soul into being as thorough a scribe as possible, quoting Deb and the rest extensively from hundreds of hours of interviews. In my final chapter, I rally readers to put pressure on the "Powers That Be" to fix a justice system that sends untold thousands of people to prison for crimes they didn't commit.

But is my rallying cry enough to make it up to Deb Brown for bringing her nightmares back?

It doesn't feel like it.

No, my debt will be paid when that cry is heeded.