It has been called a casualty of the Cold War, and the McCarthyist purge or red scare which targeted left wing activists. When the Photo League closed its doors in 1951, after being listed as a subversive organization by the U.S. Attorney General, it had already enjoyed an historic 15-year run, which helped to change the direction of American photography, and counted amongst its members some of the leading photographers of the twentieth century, including Paul Strand, Berenice Abbot, Aaron Siskind and Sid Grossman, the group's founder and philosophical mentor.

Inaugurated at the height of the Great Depression, the loose knit League turned their cameras on a world that had not been the subject of serious photography before. With the popularity of the new compact 35mm cameras, photographers no longer had to lug big view cameras and fragile glass plates around. Freed to shoot quickly and unobtrusively the ordinary life on the streets and in the workplaces of America, many seized the opportunity to document the inequities which hard economic times had brought into stark relief.

But as the show "The Radical Camera" illustrates, the progressive political agenda of the League was married to a sophisticated modernist esthetic which complemented, and sometimes appeared to compete with the group's political aims. The exhibition, jointly organized by the Jewish Museum in New York and the Columbus Museum of Art, displays straightforward photos of sharecropper shacks and antifascist rallies side by side with more formal compositions like Morris Engel's "Shoeshine Boy With Cop," a complex montage of reflections in a shop window, interlaced with figures moving on the street, conveying the frenetic energy of late 40s New York.

One of the most visually striking images, a 1939 view from above of Harlem teens playing touch football, resembles an oriental calligraphy with the boy's darting late-afternoon shadows set against the straight white center-line of the street. The photographer, Harold Corsini was criticized by some Photo League members for this too-beautiful picture, which departed from the narrative element that was central to their socially-committed photography.

Corsini's image was a part of "Harlem Document," a project supervised by Aaron Siskind to portray life in the nation's largest black enclave. Siskind's own Harlem photographs often tended toward the pure abstractions of blocks of light and shadow which would come to dominate his mature work. The photographer later expressed regret that the stereotypical views of dilapidated tenements and urban decay which the group produced failed to convey the cultural ferment of mid-century Harlem.

The show's less memorable photographs seem preachy or sometimes sentimental to us today. Yet others touch us with the nostalgic power of their witness to another age, when America's cities were more like extended villages whose social life was still conducted on the stoops, sidewalks and playgrounds. In Joe Schwartz's 1939 portrait of an Italian youth gang "The Sullivan Midgets," the boys are arrayed casually by a brownstone, with the unposed, yet seemingly choreographed elegance of a group of Matisse bathers.

Many of the photographs in the show were taken before the dominance of television, when black and white photography was still the preeminent visual storytelling medium. Unlike film and video, which show us an event in the process of unfolding, black and white photography freezes a moment from the continuum of time and holds it up for our inspection and contemplation. Images become lifted out of their context to become poignant icons for social and even spiritual realities.

Amongst the most effective icon-makers of the twentieth century was the great photojournalist W. Eugene Smith. Smith's pictures, published in photo essays in the old Life Magazine and other journals, exemplified the Photo League's ideal of engaged photography. Smith does not stand apart from his subjects, but identifies emotionally with their plight.

His images of nurse, midwife Maude Callen, a black woman working in the rural South, aimed in Smith's own words to, "Make a very strong point about racism, by simply showing a remarkable woman doing a remarkable job in an impossible situation." But they also do more than that -- they show us a human being like ourselves gazing out across the gap of a half a century suggesting profound questions about the meaning of our lives playing themselves out in the flux of time.

Race was an enduring theme in the work of the Photo League photographers. One of the most haunting pictures was taken in 1947 by Vivian Cherry of a Harlem adolescent, his head hanging limp and askew against a concrete wall, pretending to be lynched.

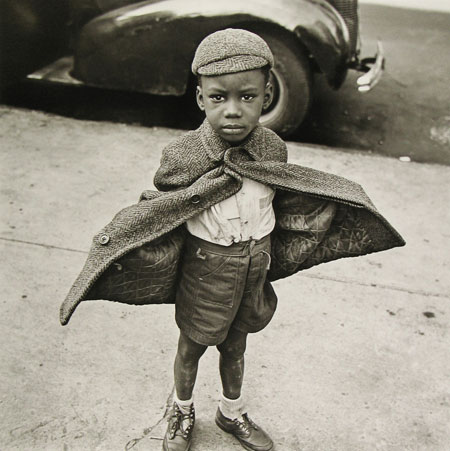

Another photo, "Butterfly Boy" by Jerome Liebling, shows a black youth his arms upraised lifting his wool coat like the wings of a butterfly as he stares intently into the camera. Who is this boy and what is he thinking? Like the best images in the "Radical Camera" we are left wondering about a life which seems at once remarkably intimate, yet at the same time oddly remote and enigmatic.

Some 60 years after the Photo League ended its run, the political points that the photographer's were trying to make touch us less than the mysterious power of a photographic image to freeze a moment -- or an entire era -- in time and bring the vanished back to life.

The Radical Camera will soon begin its national tour.

Columbus Museum of Art Columbus, OHApril 19 - September 9, 2012

Contemporary Jewish MuseumSan Francisco, CANovember 15, 2012 - February 24, 2013

Norton Museum of ArtWest Palm Beach, FLMarch 16 - June 16, 2013