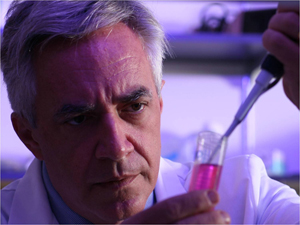

This is the second of a two-part interview with Dr. Camillo Ricordi, Scientific Director at the University of Miami's Diabetes Research Institute, and one of the world's leading scientists in islet cell transplantation. For the first part click here.

Q: What does your typical week look like, your Monday to Friday?

Dr. Camillo Ricordi: You mean Monday to Monday? In transplantation we are on call 24/7. My wife teases me because when we moved to the Diabetes Research Institute (DRI) here in Miami, I said this would mean a lifestyle change. We will be taking one week a month to go fishing in the Bahamas. We came, I bought a little boat and in 17 years I've gone fishing three times! It didn't exactly work out as I planned.

Q: I picture you in a lab or an operating room. Would that be true?

I'm mostly in a laboratory or sitting in research meetings with different research teams. But I like to do hands on work when we are testing new procedures and technologies. I'd say I'm still one of the main innovators at the Institute.

I also spend time sharing information with our international research partners and I oversee the budget. We are always looking at how to best manage our funds so we can be as efficient as possible as we move toward a cure -- the mission of the Institute.

Q: Is it difficult to get research money today?

CR: It's very difficult to get money for cure-oriented research. It's not as difficult to get funding for the corporate research we do, like testing better forms of insulin and drugs, better needles, infusion systems, insulin pumps and glucose meters. All the things that help you manage diabetes day by day, but these don't cure or eradicate the disease.

We don't get much mainstream funding for cure-focused work. For that, we rely heavily on the Diabetes Research Institute Foundation. They provide almost 40 percent of our budget. Their generous support has put us at the forefront of translational research (turning scientific discoveries at the cellular level into trials for practical application) and makes us the best hope for a cure.

Q: Are there any regulations imposed on your funding?

Yes, unfortunately the current regulatory environment hinders the type of work we do. It is extremely complex, costly and not the best way to arrive at a cure for a disease. So we developed a bridge at the DRI between academic and corporate research.

We began by setting up a collective of research institutes around the world including Asia, South America and Europe. It's called the DRI Federation. Now we can do clinical trials more efficiently through our many partners.

Q: Do you find the research world collaborative or competitive?

CR: In general, the research world is competitive. Everyone competes for a shrinking pot of money. But every scientist here signs off on our collaborative mission, that we help all other groups that have the same enthusiasm for finding a cure. We started the DRI Federation very much with this mission in mind, to expand the number of scientists who can help find a cure.

The Federation shares inventions, results, expertise, parts of equipment, operating procedures and training. For instance we will provide the blueprint for a treatment or equipment if another research institute can use it to produce something themselves more cheaply.

Many clinical trials are not done in the U.S. because of the regulatory roadblocks and cost. To do a clinical trial in the U.S. costs three times more than doing it in Europe and one hundred times more than doing it in Asia. So we're specifically expanding our collaborative efforts in South America and Asia to apply our shrinking dollars most effectively.

Q: Have you had push-back to this sharing model?

CR: At the beginning there was some. Many believed that if we had a competitive advantage, really any advantage to get funding, we should maintain it. But my aim is to reach a cure in the fastest and safest way possible. To not share, in my mind, would be criminal.

In diabetes, we have a disease that kills one person every six seconds and creates much human suffering. To delay a cure by one year because of secrecy or competition, or not helping others who may have an idea that becomes an important piece of the puzzle, to me that's unethical.

We do have to work differently today given our budget. So we focus on the key strategies we think will be successful while we keep screening for emerging new ideas that could add a piece to the puzzle for a cure. And we often redirect project teams on things that appear most promising.

Q: What's your biggest challenge?

CR: Besides funding, it's the blocking of a physician or scientist when he has the ability to cure one individual. The soldier in Afghanistan is a perfect example; If I were following existing rules to the letter, I really shouldn't have done the transplant because I didn't have the needed approvals in place at the time.

In the current regulatory environment, if you have a patient with diabetes or cancer you can only treat using randomized, evidence-based medicine, or findings from a major trial.

I went into medicine to be able to help one person at a time while concentrating my efforts on developing a cure for millions. The first few patients who had liver transplants didn't survive long, but now liver transplantation is an applied procedure for everyone. I'm not aware of any major breakthrough in the last century that would have happened under the current regulatory environment.

This environment we are working in, with the cost of health care paralyzing the execution of islet trials, it makes for a huge disappointment and concern that I have right now.

Q: I see your dedication to find a cure has not wavered. Is anything different about you since you began this work?

CR: I have much more gray hair, but along with that I have the most wonderful team in the world. We work very much like a family.

Q: At the other end of the spectrum from finding a cure, are we any closer to understanding what causes type 1 diabetes?

CR: Yes, we are a little closer to understanding the genetic contribution and environmental factors, but it's still a very complex, multi-faceted process. Likely, it's a complex combination of these. When something develops over several years like diabetes, it's much more difficult to determine the cause. Yet we are making progress.

Q: I know you're cautious about predicting when we'll have a cure for diabetes, but would you say you expect it in my lifetime, like within another 30 years?

CR: Definitely this has to be. We will have it way before you die or I die. But I think I am at higher risk for dying because I have more stress.

Q: What do you do to manage your stress?

CR: Ha, I work. I run on adrenalin and it keeps me going. I listen to music although I'm not a big fan of opera even though it is the family business. I always chose rock music over classical!

Q: Do you know what you'll do when you cure diabetes?

CR: I'll go on to the next challenge.

Q: What's that?

CR: Cancer. I already have a few ideas, but not till this job is done. Some of the work will be based on what we're doing here. I wouldn't exclude that the cure for diabetes, through autoimmunity and transplantation tolerance, will impact the cure for cancer and that they will come within five to six years of each other.

Dr. Camillo Ricordi is one of the world's leading scientists in cell transplantation. He serves as Scientific Director and Chief Academic Officer of the University of Miami Diabetes Research Institute. The Diabetes Research Institute (DRI) is recognized as a world leader in cure-focused research. Since its inception in the early 1970s, the DRI has pioneered many of the techniques used in islet cell transplantation and advances in cell biology and immunology. The DRI is now bridging emerging technologies with cell-based therapies to restore insulin production.