Fred Tomaselli

One of the most enjoyable artist interviews I ever did back in my old ARTINFO days was a piece I did with Fred Tomaselli in 2006. It's as short as any of those ARTINFO articles, and deals in most detail with technical matters, but in re-reading it, it occurs to me that it provides a useful introduction to the conversation that follows.

Mr Tomaselli is a native of Southern California and his work bears the evidence of the very particular cultural experiences of growing up in that part of the world. He is best known as the maker of stunning large scale, intensely colored pictures that are almost overloaded with meaning. He makes them by assembling collaged and painted images and occasional small objects that he embeds in layer after layer of resin. Among these embedded objects are - somewhat infamously - pills and marijuana leaves, which have led to the erroneous assumption that all of his work is drug fueled. Though his subjects are often dream-like, they are equally often based in natural phenomena or the history of art. As he explains here, it is simple minded to think of him as just a psychedelic artist.

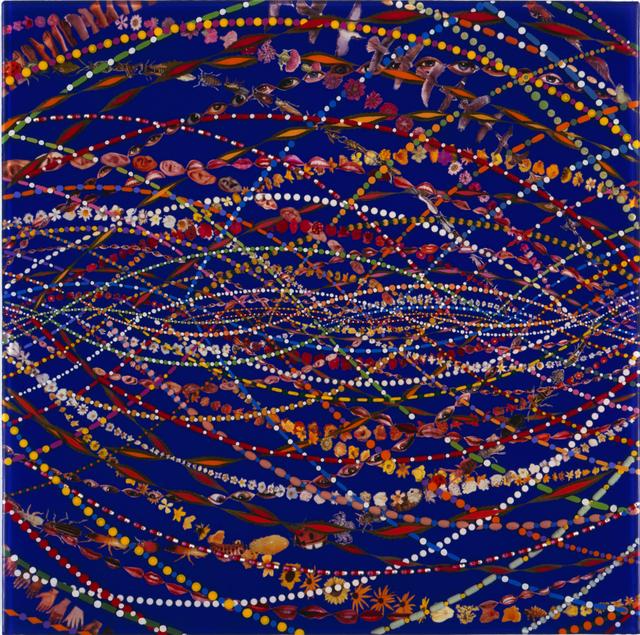

Fred Tomaselli, "Doppler Effect in Blue" (2002)

Mr Tomaselli is represented by James Cohan in New York and by White Cube in London. Through January 2, he is the subject of a deeply satisfying retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum (which was shown previously at Aspen Art Museum and the Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College). It is accompanied by a beautiful catalog that has been co-published with Prestel. I spoke to Mr Tomaselli earlier this month and as ever, he proved to be a pleasure to talk to: funny, intelligent, self-deprecating, and eager to drag a whole range of unexpected cultural references into his conversation.

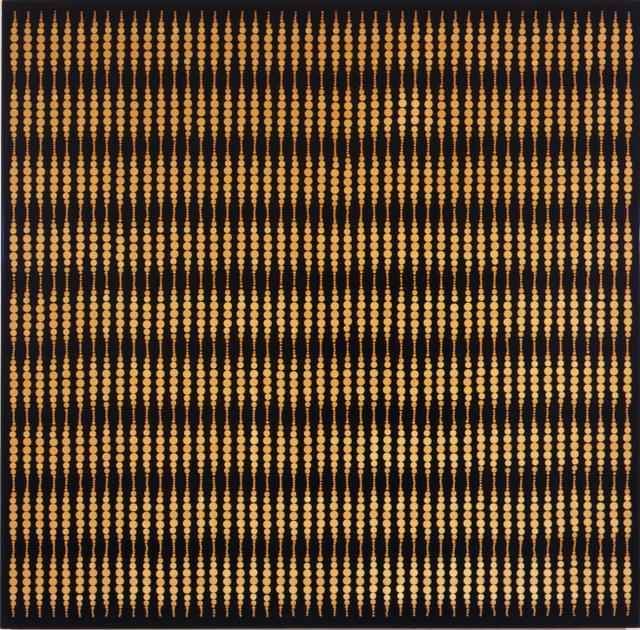

Fred Tomaselli, "Black and White All Over" (1993)

Fred, I very much enjoyed seeing your Brooklyn Museum show. There was a lot of the work there that I had never actually seen before, particularly the early stuff that had an almost minimalist look to it.

That work initially came out of conceptual ideas that I had about paintings and perception. At the time I executed the objects in a very straightforward manner and yes, I was utilizing minimalist tropes. The big change in the work came as I started adding the atrophied painting skills that I had accrued in art school but then abandoned because of the burden of history. So rather than the work being executed in the very deliberative way of the initial works, they became more and more "arrived at": I wouldn't know exactly what I was doing, and an intuitive evanescent impulse increasingly took over. That's the difference between the earliest works and the latest works.

Fred Tomaselli, "Migrant Fruit Thugs" (2006)

And they seem increasingly joyous, and wide-ranging in their sources - pieces like Migrant Fruit Thugs always remind me of medieval tapestries.

Yes. I think there is a sense of joy in the work about being alive, and opening up your senses to experience, to the overwhelming sensations of lushness in the world. That's always there. And yes, The Unicorn Tapestries in the Met are certainly one of the many influences that have come into the work. It's not just painting.

What else is it?

It's a whole bunch of other stuff. Initially the work was all woodworking. It was all inlaid marquetry. If you look really closely you'll see that some of the earliest things are full of routed slots and drilled holes that came out of my day-job as a woodworker, which gave me the ability to utilize the tools.

And as you know I came out of surf culture in Southern California. We all used to shape boards so I've been conversant with how to use resin - pouring the stuff and using it with fiberglass - since I was about twelve! It was part of the working class beach culture of Southern California. Plus there was the car stuff. I worked my way through art school as an auto mechanic, doing various stuff including sanding bodywork and using Bondo filler. In fact the same things that were inspirational to the Southern California Finish Fetish movement were also part of my background.

So car culture, surf culture, as well as tapestries and furniture making were all non-painterly, applied art ways of making objects that factored into the look of my work.

I think it's funny though - both the car and the surfboard are vehicles of transportation that take you from one place to another. That absolutely comports with my ideas about paintings as windows to other realities. I do think of these pictures as transportation vehicles that take you to other places.

How do they do that?

I think that there are pathologies, little viruses squirming around in the work, that you don't see right away.

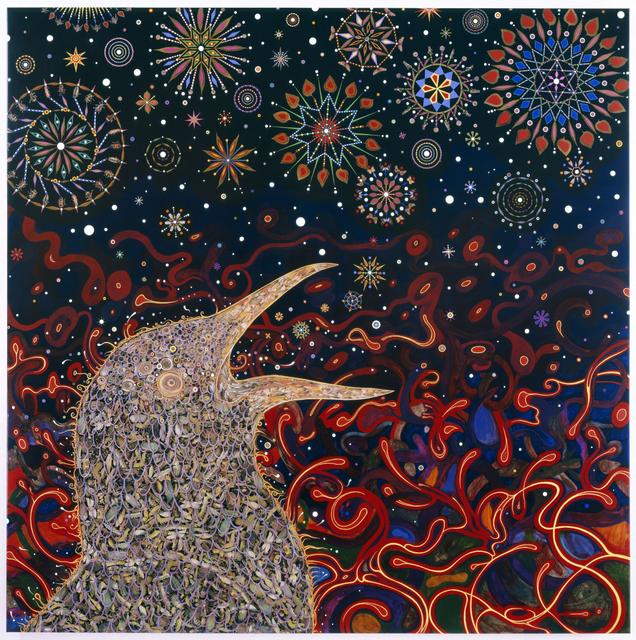

Fred Tomaselli, "Starling" (2010)

And how do we become aware of them?

I've come to believe in the primacy of form - the notion of art seducing you through your senses, through your eyeballs. It's akin to a melody in a song. That's the thing that pulls you into a song, and then later you listen to the words, and if they're any good that makes for a great, full-bodied, wonderful listening experience. There's something for your aural body, and there's something for your head. The idea of form (or visuals) first always appealed to me. Then later people think about what it means, and what else might be behind the work that can enrich the experience.

Yes, that seemed to be exactly how people were enjoying your Brooklyn show.

There is this non-art world audience that goes to the Brooklyn Museum. I don't know if I'm a populist artist, but I do try to maintain a spirit of generosity. I try to put as much into the work as possible. I try to overload it so that you can never get to the bottom of it, hopefully. In a funny way, it's like the idea of a gift economy. I feel I've been given the gift of all these voices, all these authors in my work - all of the photographers and illustrators and all their images and objects that flow into the work - that I use and get to be the conductor of. It all comes out of the world and my experience of it, and I love bringing it back into the world and back to normal people. It's part of a notion of democracy that I believe in. And the spirit of democracy is not necessarily something that I think of when I think of the art world.

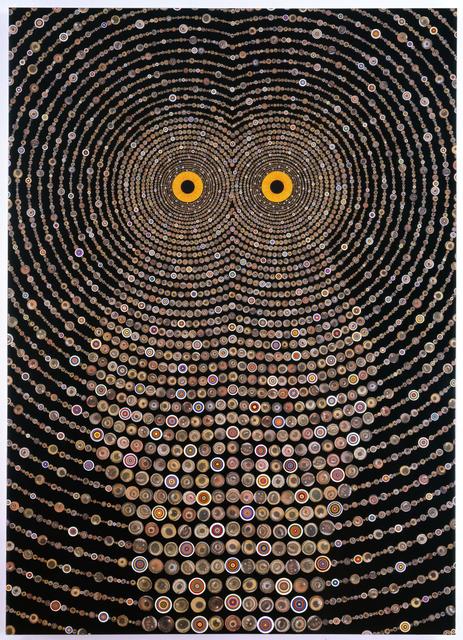

Fred Tomaselli, "Night Music for Raptors" (2010)

Do you feel your work sits more comfortably outside the art world?

It is funny that the art world is the only place where the term "beauty" can be used in a pejorative way. Can you think of any other place where beauty would be construed negatively? It's only in the art world where beauty becomes suspect. We like to think of ourselves as tough-minded modernists, wrestling with truth. That's all fine and I have nothing against that, but once you make something beautiful, or you're responding to the beauty of the world, then all of a sudden it becomes suspect. It becomes bourgeois or it becomes too easy. I'm not sure that I buy that.

Fred Tomaselli, "Passerines White Eyes" (2003)

There's also the question of humor in your work.

Well, I think that's another layer of seduction that I practice. A lot of people don't think of my work as being all that funny, but I think it's hilarious! I think that the humor in the little bird paper works is relatively self-evident. And I think that the whole idea of inserting drugs into objects, so that instead of going through the bloodstream to affect the consciousness they travel through the eyeballs, I think that's funny. Or absurd at least. I think there's a whole level of absurdity built into the work that I think is amusing. I don't know if other people get it, but I think it's funny. Do you think it's funny?

Yes, and refreshingly free of theory, which is almost as important!

It's an odd thing about theory because, coming out of Southern California in the 80s, I was quite friendly with a lot of the CalArts people. We would bat around ideas about Baudrillard and Barthes and Debord, and about the culture of signs and The Society of the Spectacle and art in an age of reproduction. It did give me a way of thinking about how art functions, and how perception is modified in this culture of the unreal that we live in. But it's funny, I think that when my work was really bad it was because it was in thrall to all of that. (I threw away a bunch of that stuff this week, so I know what I'm talking about!) But it's fascinating, because it allowed me to start thinking about pictures and how they work. But when I actually started making the stuff that I'm making now, what became really important wasn't the theory any more, it was my own personal experience and how that reckoned with the culture, and with art history, and with theory. The more I put myself into the work, the less important theory was to me. Now it's barely there, at the very bottom of this palimpsest of other information. I basically just used all the other information that came out of my life, and that's what made the work good. I wish other artists would pay attention to their lives. It would make art more interesting, don't you think?

Fred Tomaselli, "Feb. 3, 2009" (2009)

Undoubtedly! Tell me, to what extent is politics part of the life experience that feeds into your art?

I'm a pretty politically engaged person - I'm not a total escapist! A lot of people have been commenting about how political those New York Times works at the end of the show are. I guess that some of them are more political than others, but I like the idea of the world going to hell around me while I'm still painting. That's the most political thing about them in my opinion. I was thinking about Juan Miro when he was doing the constellation drawings during World War II, which are some of his most cosmic things. There's something incredibly moving about those images that are so beautiful and so cosmic and so luscious, made while the depravity of the second world war was going on around them. It's a sort of framing around the work. I like the framing of the world going to hell in a hand basket and I'm still painting away.

I also think I'm tapping into a strong undercurrent in American culture (and Europeans tell me I really do apply an American experience to the work). It's the idea of teetering between ecstasy and apocalypse, which I think is part and parcel of a particularly American experience. It occurs elsewhere, but you see the balance of apocalypse and ecstasy (where we have hellfire and brimstone preachers on the one hand, and Thoreau and Emerson and the birthplace of transcendentalism on the other) playing out continuously in this culture. And I do feel like I'm tapping into that history, that wobbling right on the edge, on the brink of those two oppositional places. But you know, I think ecstasy generally wins!

Well, that brings us nicely to what used to be another cornerstone of your painting. How do you feel about their drug-derived aspects these days?

They ground the work in a particular experience that I found dovetailed uncannily with art historical ideas about art and perceptual modification. I found these corollaries between low-culture stonerism and high-culture pre-modernism. I have been truly changed by my immersion in psychedelic drugs, and drug culture in general, and I put that into the work.

But I do disagree a little bit with people constantly calling me psychedelic artist. I know that there are tropes that I fall into that make that a pretty easy thing to say, and I've certainly utilized the shape of that experience in the work, but I think that a psychedelic artist is really trying to bring something back from the other side of that dimension that they go to. I'm not really trying to do that. I'm trying to use the experience to talk about perception in art and how I see the world, but that's not where it stops. People say that I'm a really good psychedelic artist, and they have a tendency that when they can label something they dismiss it. I prefer that they look into it a little more deeply.

There's a lot of influences in the work that came out of psychedelia and the kitsch that was a part of psychedelia - the album covers and all that hippy stuff that I grew up with. But it also was a gateway into Islamic art and Persian art, into Rajasthani miniatures and folk art.

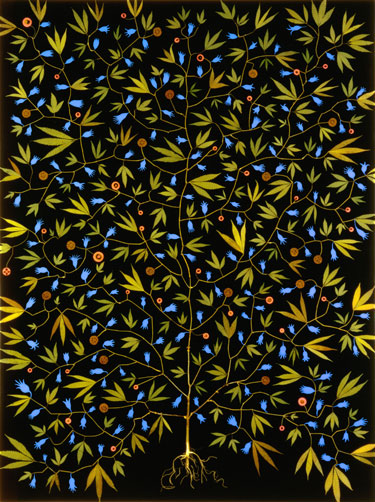

Fred Tomaselli, "Super Plant" (1994)

There's one work in particular, Super Plant, that oscillates between Rajasthani miniatures and the Shaker tree of life, between and eastern mysticism and Americana. Those things are part of the work, but I don't necessarily think of them as psychedelic. They're just deep art history.

So much of what constitutes the post-modernist production that's so groovy right now maybe goes back to Duchamp. Warhol and Duchamp seem to be the operative influences on so much contemporary discourse, and I just wanted to go a little further into history. But then people dismiss the work and call me a psychedelic artist, so what are you going to do?