First they threw popcorn at her in the cafeteria. They mocked her accent and limited English. They probed her for Spanish translations of curse words to fling back. They filed bogus complaints to intimidate her into believing she would be forced out of the nursing home. Two months prior, two residents at my mother’s nursing home in northern Colorado began overcrowding her table at dinner time, making it uncomfortable for her to sit or eat. And when she complained informally to a staff member, the couple launched a full-on assault.

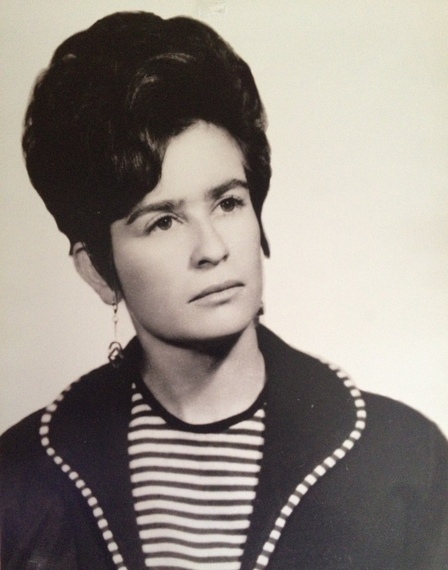

It's Older Americans Month, a time to honor the contributions of older people to this country. I choose to honor my mother by describing the life that she carved for herself—and how she still fights to survive.

At 13, my mother lost her own mother to childbirth complications. To survive financially, she dropped out of school and helped her widowed father raise her four siblings, selling small merchandise at a local market in León, Guanajuato, Mexico. Perhaps this early life moment would influence her to become a pharmacist in her early 20s, where she secretly sold contraceptives to women in her neighborhood who had grown tired of having children—a risky enterprise in a socially conservative, predominantly Catholic country. My mother taught me to root my practices in the needs of the most vulnerable. She taught me to defy harmful norms and the sanctions imposed upon us. She taught me to honor the people we lose from our lives by aiding those who live on.

In 1969, at age 30, she left Mexico for Los Angeles in pursuit of more income and a different life. Her hometown friends in L.A. hired her for their small housekeeping business, effectively stealing most of her income through employer deductions. Fed up and exploited, she quit a few months later, boarded a bus back to Mexico, met my father in the seat next to her (who was on leave from the Vietnam War), and fell in love in mere hours. For months, they mailed each other photographs, letters, poetry and postcards. They wed the following year and moved to Sacramento, California, then Pueblo, Colorado, where I was born. They remain married to this date. My mother taught me about writing one’s script when love seats itself next to you; the soul craves nothing if not risk or faith. She taught me that migration is comprised of tinier journeys that we tote in our pockets, embraced or dispensed as we will. She taught me that one must learn when to keep moving and when to hold still.

My mother began taking citizenship classes at a local library in the early 1980s. A few white librarians disapproved of the classes taking place in their basement, so they would follow my sister and me through the library while we waited for our mother, snatching books from our hands and citing inane visitation policies. On some days, we would wait defeated and distraught in our worn-down Oldsmobile. On other days, we sauntered through the aisles, flaunting our youthful doggedness. My mother would go on to ace her naturalization test. The day of her naturalization ceremony, she held onto a small American flag in one hand and my father’s hand in the other. Though my father’s war stints in Korea and Vietnam had seeded a well-earned distaste for patriotism and a necessary critique of American foreign policy, he knew enough in that moment to admire her achievement. My mother taught me that the best rebuttal to those who seek to annihilate us is to simply succeed. She taught me to saunter. She taught me to hold my personal love and my political ideology in each hand, to clasp them repeatedly until I understood when to unloose them.

The decades that followed reappear as celluloid frames. In 1982, she suffered a series of devastating strokes that left her immobile for six months and with permanent peripheral vision loss in her left eye. She published her first and only collection of poems in Mexico five years later. She lost her sister, father and brother to deaths that were mourned largely from a distance. In one rendering, she's vivacious and loud, rattling off self-deprecating jokes and trying to gratify my father's more acculturated Latino family. She's a gender non-conformist who refuses to wear makeup or dresses. She’s a soccer player who challenges the men in our family to backyard soccer bouts that she readily wins. I can hear her taunts and cheers. I can perceive her demands for academic perfection, explaining that we must always try harder than our white peers just to be perceived as equivalent. My mother taught me to outmaneuver the elites in my career who will heedlessly block me. She taught me to kick and score goals. She taught me to be disciplined and resilient, as original as the unapologetic world we were born to repair.

And then this memory. It's New Year's Day, I'm 22, a sophomore in college, and I'm coming out as gay to her only hours after the lunch table has been cleared. She's stolid in her immediate response: she supports me; she fears I'll die of violence or AIDS (an ignorance and stigma that dissipates in her over time); and she requests that I withhold this news from her family and seek short-term counseling. That night, she tucks a two-page letter in my suitcase where she emphasizes that her love for me is nevertheless unequivocal, regardless of the man I become or the man I will one day bring home. The letter is florid in language and form. It blooms in front of me with its raw and fragrant heart. My mother taught me that confessions are gifts as precious as their reactions.

And now, nearly two decades later, she confesses her own dilemma: Two residents in a nursing home are making her life miserable. I’m infuriated. My role as a national LGBT aging advocate has shown me that elder abuse is a pernicious epidemic, one that feeds off the smaller support networks and profound isolation of more marginalized older people who lack the ecosystems or wherewithal to fight back. It can couple with poverty, racism and homo/bi/trans/phobia to destabilize the psychological, physical and financial lives of elders, especially those who are low-income, people of color and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT). It comes from strangers and predatory financial professionals and con artists, but most often it comes from those nearest to us.

Before I can respond, my mother jumps ahead to its ending. Undeterred by the abuse of these two residents, she attended the next meeting for nursing home residents and advocated successfully for this couple to be removed from her table. Today the couple eats alone in their shared room, away from my mother’s table and displaced from the entire cafeteria of residents. I love my mother, and I loathe any form of abuse. I’m also fond of self-advocacy tales where people tackle their oppressors. These stories keep me alive. They keep this country’s unfulfilled promise alive.

Yet as she imparts this final detail, I detect both pride and sadness in her voice. On one level, the insidious power of abuse is that it can make even self-defense feel like another form of defeat. On another level, I suspect that the image of this couple dining alone haunts her in the same way it haunts me. We know nothing of this couple’s lives—nothing about their relationship, their aspirations, their accumulated losses or their mental health. They too must have a life trajectory marked by wounds undetectable.

Was this problem permanently solved? Will the couple retaliate? Did the facility miss its chance to unpack the underlying motivations for this abuse and mediate an approach that respected everyone involved—while still emphasizing my mother’s safety? Does the facility staff have the willingness, skills and resources to address abuse among residents, particularly when dealing with the heightened barriers among Latino people with limited English proficiency? And has this nursing home been systemically defunded over the years by the larger corporate and neoconservative attack on the social safety net? Is this facility—its management, staff and residents—one more casualty in the national underfunding of eldercare, elder abuse, and aging services and supports for more marginalized seniors?

These issues might also reflect our point in time as a country still grappling with the growing number of older people in the US. A colleague of mine suggests that the typical response in elder abuse cases has historically been punitive and prosecutorial, especially in cases involving financial exploitation. Also, because a large majority of elder abuse perpetrators are family members and caregivers—scenarios where an entrenched power discrepancy exists for a variety of factors—there might be less attention on implementing the existing guidance for dealing with elder abuse among elders living in long-term care facilities. Nevertheless, this lack of sufficient interventions is fatal; the National Center on Elder Abuse reports that those who experience even modest elder abuse have a 300 percent higher risk of death than those who have not been abused.

Statistics aside, is it simplistic for me to posit that some forms of elder abuse can be understood as the clash between people whose life stories yielded dramatically different outcomes? I’m not rationalizing specific incidents of elder abuse; my primary allegiance is with the person suffering the abuse. I’m asking whether we know—as aging advocates, as family members, as policy leaders and as fellow residents in long-term care settings—enough about our worst selves to understand what it means to overcome the persistent abuse we too often inflict on each other. After all, it was Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who argued that when “we look beneath the surface, beneath the impulsive evil deed, we see within our enemy-neighbor a measure of goodness and know that the viciousness and evilness of his acts are not quite representative of all that he is. We see him in a new light." In that essay, Dr. King goes on to reason that “love is the only force capable of transforming an enemy into a friend.”

I don’t have the requisite answers—and that’s the point. My mother taught me that impossible questions can reap more possible truths. She taught me to cradle one’s conscience near the chest, where the soul is as essential as the heart. The heart circulates the blood that enlivens every cell in our bodies. It pulses with indecipherable yearning. The soul, in turn, harbors what we’ll need to sustain our momentary existence. It divulges why each of us matters, what we must fight for, and what must go on.