Over the past few decades, we've learned the hard way that once manufacturing is gone, engineering know-how quickly follows, and then later on innovation and our national security suffers the consequences. That's a place that America has never been before.

In May of 2012, the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee reported more than 1,800 cases of suspected technological counterfeiting, involving more than 1 million parts for some of our country's "most important military systems." At the same time, the 2012 Defense department report confirmed that the most advanced work for many technologies is no longer being conducted in the United States at all.

Offshoring was once regarded as a clever new way to improve one's bottom line, but strategizing around wage differentials, currency rates and transportation costs can only ever provide a momentary bump on a stock report and is anything but a robust solution. Millions of manufacturing job loses in the last decade are largely a result of outsourcing, with hardly any due to productivity gains as claimed by some.

Even some experts, who had in the mid-90s promoted a "China plan" for U.S manufacturers as a necessary strategy to cut costs, are now touting re-shoring back to the U.S., although benefits of reshoring are little more than anecdotal. It's true that wages in China have been steadily rising at 10-15 percent per year but they are still a small fraction of U.S wages. And besides, in a global market, as China's wages grow, low-skill labor will simply move to another even lower wage country. As much as we might wish it, reshoring is not going to replace all that we've lost; and "silver bullet" solutions like 3D printing are not going to revamp a $2 trillion American manufacturing economy anytime soon.

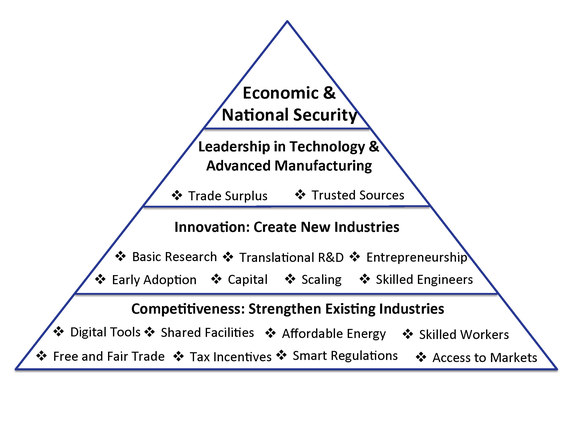

America's comparative advantage in high-technology products, engineered and manufactured by our world-class engineers and highly skilled workers, is the only sustainable model that has ever worked. This is because in high-technology industries, manufacturing and R&D are closely bound. Once the manufacturing process is matured, design and manufacturing can be separated -- that is, manufacturing can be outsourced. Hence it is important to establish the needed infrastructure as the technology is being matured so that manufacturing can take root alongside R&D. Ample evidence shows that combining the two is key to fueling real innovation, and the co-location of R&D and manufacturing facilities adds value to each. History has shown many times that failure to manufacture a generation of such products puts the ability to innovate the next generation of products at risk.

We need to re-establish a robust manufacturing sector by rebuilding the knowledge, skills and infrastructure to create and maintain new supply chains for next-generation products by leveraging our inherent strengths in government-funded basic research, entrepreneurship and free markets.

Role of Government

Although some say that "government should not pick winners and losers" and "get out of the way," of American private enterprise, it's worth remembering that historically our government has always nurtured the creation of new high-technology industries, often by underwriting basic and translational research, development, demonstration, and early procurement.

A highly illustrative example is America's aircraft industry. A dozen years after Orville Wright took his Flyer airborne at Kitty Hawk in 1903, the United States lagged behind other nations in the emerging aviation industry. In 1915, the federal government established the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) to advance the standards, design, and development of engines and airfoils. By 1916, American companies had produced only 411 aircraft, but we churned out more than 12,000 in a nine-month period from 1917 to 1918 to close out WWI. Then as now, defense procurement has proven highly successful at accelerating innovation.

Similar government investment led to our leadership in semiconductors, computers and the Internet though we've failed to leverage the fruits of more recent innovations such as cell phones, flat panel displays and lithium-ion batteries, to name but a few. This was at least partly due to a lack of timely investment by government and industry in the translational research needed to reduce technical and market risks and bolster those budding markets. The U.S. is creating knowledge but failing to create wealth and jobs with technologies that we've largely invented.

To be sure, the initial spark for new industries comes from the genius of individual entrepreneurs, scientists and engineers, but it sometimes takes a bit of federal support to fund high-risk R&D in order to overcome market failures, and the hesitance of established firms. Risk-averse corporate R&D has declined significantly in the last two decades and is now mostly limited to product development (otherwise known as "applied" R&D). It can be characterized as incremental at best and tends to focus on making current products more profitable. This is not so much a character flaw as a survival tactic for our increasingly timid corporate behemoths.

Simply investing in basic research and leaving the rest to the free market has not worked in recent decades in a globally competitive world. It has left an innovation gap between discoveries and manufacturing. Once our "nascent" technologies begin to mature and their manufacturing /supply chains take root elsewhere, it is not only difficult to bring them back but worse, the next generation versions are now being invented over there.

Investing in the Future

President Obama's Manufacturing Innovation Institutes are meant to bridge this innovation gap by investing in translational R&D to mature emerging technologies and their manufacturing readiness. Modeled after Germany's Fraunhofer institutes, which in turn were inspired our own "Bell Labs" of yesteryear, the Manufacturing Innovation Institutes identify and avoid market failures and are funded jointly by the government and the private sector. The first of these institutes was established in 2012, three more were announced earlier this year, and the President has proposed a total of 45 over the course of the program. These institutes are not designed to bring back all those millions of middle-skill jobs we've already lost. The mission of these public-private partnerships is to leverage new discoveries and inventions that could lead to the next big thing and lay the foundations for next generation high-tech products so we don't lose them as well.

We may not yet know what "next big thing" these technologies will lead to; but public-private partnerships, such as Manufacturing Innovation Institutes, should be put in place to avoid market failures by supporting emerging technologies that offer (a) high growth potential and broad economic impact and (b) a "first mover" advantage relative to international competitors. We have to be careful not to let these institutes shift their focus away from the translational R&D needed to create new industries.

When it comes to existing industries, cutting edge technology, more often than not, plays only a secondary role. Ineffective trade policies can tilt the playing field against U.S. manufacturers (steel, solar cells, for example) and this leads to further erosion and sometimes, loss of a whole sector's growth, jobs and key supply chains. In addition to fair trade and smart regulations, we need a skilled workforce and affordable energy to stay competitive.

The training of skilled production workers should also be a shared responsibility between public and private sectors much like the Manufacturing Innovation Institutes. Leveraging federal investments, the private sector must engage with community colleges and municipalities to craft training programs for employable skills, and revamping internships and apprenticeship programs. Consider that, despite cries from domestic employers at the lack of a skilled domestic workforce, foreign manufacturers like Siemens, BMW, and Toyota routinely invest in their own workforce training and are managing to thrive in the U.S.

This Administration's focus on advanced manufacturing comes at a uniquely advantageous time with the development of low-cost natural gas and natural gas liquids (NGLs) in the U.S. We need a comprehensive national strategy for sustainable use of shale gas to promote economic growth and jobs. For a brief window we have reduced feedstock costs for U.S. chemical industry and reduced energy costs for America's energy intensive manufacturing sector such as steel, aluminum, paper, glass and others by as much as $11.6 billion per year. This shale gas boom has already supported 2.1 million jobs and added $283 billion to GDP last year. The hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling technologies that enabled the shale boom are examples of American ingenuity and decades of R&D funded by public and private entities.

Anchoring Manufacturing in the U.S

As we excel in creating knowledge we must get better at converting that knowledge into American jobs and wealth through public-private partnerships on initiatives like Manufacturing Innovation Institutes.

But that is still not enough -- because there is no guarantee that the resulting new products and processes will take root in the U.S. For that, we need legislation that encourages establishing new manufacturing facilities in the U.S. as well as financial disincentives for moving them overseas. We need to ensure a net return on the taxpayer investments that helped develop the technology in the first place.

In cases where companies still prefer to manufacture outside the U.S., they should do so by returning a percentage of their offshore profits to the U.S taxpayer as compensation for the systems or components that were developed through those government-funded technologies or their derivatives. Without some type of legislative teeth to promote domestic manufacturing while discouraging offshoring, the benefits of our investments in basic and translational R&D will not trickle down to strengthen our economic and national security. And as with any "investment," in contrast to "spending", appropriate metrics and effective oversight polices will be needed to measure our return.

Many of the ingredients we need to restore a robust American manufacturing power base are still intact. If enough leaders, of all stripes, in Washington and in industry, can make the strategic commitments necessary, we can regain our manufacturing prowess through public-private partnerships built on a solid foundation of basic & translational research to create new industries and fair and sustainable trade, taxes and regulation to enhance competitiveness of existing industries. The time is right, and the creativity and entrepreneurial spirit in America's collective DNA are still second to none.