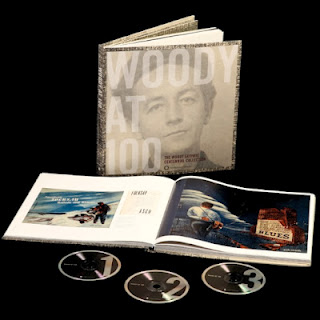

Smithsonian Folkways recordings has released Woody at 100, an impressive box set that will greatly enrich our understanding of the great American artist, Woody Guthrie. The lavish, 150-page hardcover book, accompanied by three CDs of Guthrie's best recordings, will provide enthusiasts and novices alike with hours of joy and some good food for thought.

Smithsonian Folkways recordings has released Woody at 100, an impressive box set that will greatly enrich our understanding of the great American artist, Woody Guthrie. The lavish, 150-page hardcover book, accompanied by three CDs of Guthrie's best recordings, will provide enthusiasts and novices alike with hours of joy and some good food for thought.

The book contains an eloquent introduction by Robert Santelli of the Grammy Museum, and a meaty essay and detailed track notes by Smithsonian archivist Jeff Place (himself a multiple Grammy winner). More importantly, it includes full-page illustrations of Guthrie's work: pen-and-ink cartoons, brush-and-ink paintings, illustrated letters and lyric sheets (both typed and handwritten), and even a remarkable oil painting of Abraham Lincoln. Other graphic elements include contracts and telegrams, LP labels, photographs of Woody and his friends, and reproductions of album covers, all tied together with first-rate design. The set would be worth it as a book of artwork, poetry, and correspondence by an American Master.

Just one quirky item in it that sheds new light on Woody is a 1949 letter to Folkways executive Moses Asch and his secretary, Marian Distler. At the time, Woody's song "Philadelphia Lawyer" had just been covered on records by his friend Cisco Houston and the West Coast band, The Maddox Brothers and Rose. Woody urges Asch to release his original recording of the song, since these cover versions are bound to make it popular. He then rhapsodizes at length about the Maddoxes: "This is the best all-around hillbilly band I've heard in my life," he writes. "They do everything from lowdown blues up through silly nonsense songs, and on to serious spirituals, and ballads with a pretty fair content, and do the best job I've so far heard done by any hillcountry band."

Woody then shifts gears. Worrying that he might soon be indicted for sexually explicit letters sent to a female friend, he offers this advice to Asch and Distler: "Take all your obscene feelings out in spoken words on each other. Don't never write them down and drop them into no public mail box." (Guthrie was indeed indicted and then convicted of sending obscene materials through the mail, ultimately spending ten days in jail.) The letter is adorned with one of Guthrie's deceptively simple brushstroke cartoons in red ink, showing a perfectly round moon, with a surprised-looking face in it, hovering above stylized brownstones. (The letter was posted from Brooklyn on May 13, 1949... the morning after a full moon.)  The first two discs present Guthrie's greatest hits; most of them come from Folkways, but some are from the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. They include traditional folk ballads ("Gypsy Davy," "Bad Lee Brown"), Guthrie's own adaptations of folklore themes ("Buffalo Skinners," "The Greatest Thing that Man Has Ever Done"), a few kids' songs ("Riding in My Car," "Howdi Do"), a wide range of topical songs ("Talking Dust Bowl," "Sinking of the Ruben James," "Lindbergh"), and a wealth of songs dealing with labor and Woody's political beliefs ("Jackhammer John," "Farmer-Labor Train," "Jesus Christ"). They present a fascinating and rounded portrait of Guthrie, but it's the third disc, presenting largely unreleased material, that's likely to excite Guthrie fans. The biggest deal is the inclusion of four songs recorded on instantaneous discs by Guthrie in the late '30s in Los Angeles, probably his earliest recordings of any kind. Their existence was known only to a very few people until they were uncovered by historian Peter LaChapelle in 1999 at an LA library. Two of them, "I Ain't Got No Home in this World Anymore" and "Do Re Mi," chronicle the experience of Dust Bowl refugees, and became well known through later versions. The others, "Skid Row Serenade" and "Big City Ways," show the other side of Guthrie in the 1930s, the proud country boy forced to live in the big city. After adapting to the city, he dropped them from his repertoire and they were never heard until now.

The first two discs present Guthrie's greatest hits; most of them come from Folkways, but some are from the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. They include traditional folk ballads ("Gypsy Davy," "Bad Lee Brown"), Guthrie's own adaptations of folklore themes ("Buffalo Skinners," "The Greatest Thing that Man Has Ever Done"), a few kids' songs ("Riding in My Car," "Howdi Do"), a wide range of topical songs ("Talking Dust Bowl," "Sinking of the Ruben James," "Lindbergh"), and a wealth of songs dealing with labor and Woody's political beliefs ("Jackhammer John," "Farmer-Labor Train," "Jesus Christ"). They present a fascinating and rounded portrait of Guthrie, but it's the third disc, presenting largely unreleased material, that's likely to excite Guthrie fans. The biggest deal is the inclusion of four songs recorded on instantaneous discs by Guthrie in the late '30s in Los Angeles, probably his earliest recordings of any kind. Their existence was known only to a very few people until they were uncovered by historian Peter LaChapelle in 1999 at an LA library. Two of them, "I Ain't Got No Home in this World Anymore" and "Do Re Mi," chronicle the experience of Dust Bowl refugees, and became well known through later versions. The others, "Skid Row Serenade" and "Big City Ways," show the other side of Guthrie in the 1930s, the proud country boy forced to live in the big city. After adapting to the city, he dropped them from his repertoire and they were never heard until now.

The set continues with radio broadcasts, which give a fun sense of Woody's experiences as a hobo and a merchant sailor: traditional sea chanteys in one show, train songs in another. (A comically prim and proper BBC host makes for a great contrast with Woody's laconic drawl.) Another track includes repartee between Guthrie and Lee Hays at a concert of the Almanac Singers, with Pete Seeger's banjo audible behind them. The set concludes movingly with "Goodnight Little Cathy," a song Guthrie wrote for his daughter; after Cathy Guthrie died at the age of four, the song was reworked into "Goodnight Little Arlo."

The set continues with radio broadcasts, which give a fun sense of Woody's experiences as a hobo and a merchant sailor: traditional sea chanteys in one show, train songs in another. (A comically prim and proper BBC host makes for a great contrast with Woody's laconic drawl.) Another track includes repartee between Guthrie and Lee Hays at a concert of the Almanac Singers, with Pete Seeger's banjo audible behind them. The set concludes movingly with "Goodnight Little Cathy," a song Guthrie wrote for his daughter; after Cathy Guthrie died at the age of four, the song was reworked into "Goodnight Little Arlo."

The broadcasts show that Guthrie was renowned for singing traditional songs. This is important: It's largely because of his performances of traditional folk songs that Woody was accepted as a "folksinger" by such authorities as John and Alan Lomax at the Library of Congress. In turn, the fact that this renowned "folksinger" was a singer-songwriter is largely responsible for the shift in meaning of "folk" in American music, from traditional music to acoustic singer-songwriters. Not many people can claim to have helped change the meaning of a common word, but I think Guthrie can.

Woody at 100 suggests fascinating questions about Guthrie's most iconic creation, "This Land Is Your Land." The first disc contains two versions: the standard version, recorded in 1946, and a 1944 recording containing the famous subversive verse about ignoring a "Private Property" sign:

(Another verse, in which Woody comments on seeing "his people" on depression-era breadlines, was taught by Woody to his children, but never recorded.)

The third disc contains another variation, sung as his radio theme song:

"This land is your land, this land is my land

From the redwood forest to the New York island

The Canadian mountain to the Gulf Stream waters,

This land was made for you and me."

Interestingly, this is also how Guthrie first published the lyrics in 1945. Place has elsewhere suggested "the Canadian mountain" was added on the fly, for a recording on which Guthrie and Cisco Houston narrated their adventures as hobos. Surely, though, if Guthrie published this chorus in his songbook, and sang it as his radio theme, it must have been his preferred chorus, at least for a time.

Is the "Canadian mountain" significant? Like the "Private Property" verse and the breadline verse, it suggests that Guthrie denied the boundaries that divided "his people," be they boundaries of class, property, or nation. Along with the title, this chorus shows us that Woody's America is not a nation but a land, which doesn't end at the Great Lakes or the Rio Grande, but rolls across the northern mountains and through the southern valleys, echoing with songs.