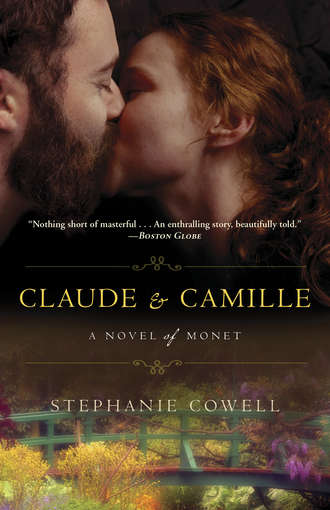

Stephanie Cowell writes lush and compelling fictional portraits of the world's greatest artists, writers, and composers: their struggles, their liaisons, their failures and successes. Claude and Camille, her book about Monet's star-crossed marriage to his enigmatic muse, will be released in trade paperback this week after selling well in hardback and ebook. Cowell is now working on her sixth novel about two immortal poets whom she mentions below.

A native New Yorker, Stephanie Cowell lives in Manhattan with her husband, Russell Clay, a poet and reiki master. Prior to 1993 when she published her first novel, Nicholas Cooke, she sang opera with various chamber companies, worked as a freelance balladeer, and raised two sons. Recently, Cowell took a few moments from her bustling schedule to chat by phone about her creative process, her background, and her next book.

You've mentioned that your parents were artists. Is this what drew you to Claude Monet?

Writing about Monet's life in his twenties so absorbed my life that it is hard to remember when I did not know a lot about him. Of course my parents always took me to museums, and fifteen years ago I went to the Metropolitan Museum and first became aware of the young Monet. I was so drawn to the painting of darkening skies and weary horses on a shore in Le Havre where he was born, I said, 'Who was that young man?' It was nothing like the water lily paintings. I was fascinated.

What aspects of Monet's life, talent, and temperament do you think Claude and Camille can dramatize more subtly or dynamically than a biography?

Novels can bring historical figures to life with an emotional immediacy and intensity which no biography can do. A biography might say, 'The young artist struggled hard in those years.' In the novel we see him in his shabby room, hearing the bailiffs breaking in the door because he has not paid his rent, and we feel his anger and fear. A biography might say, 'He fell intensely in love with the nineteen-year-old Camille,' but a novel can show his insecurity and intense sexuality as he looks at her for the first time. In a novel we are with the person as he or she feels things; hopefully, we feel them too.

You wrote about Monet's first wife and muse, Camille Doncieux, and yet little is known about the real Camille. Do you have rules for creating fictional portraits of real people?

As much as possible I keep to the known character and life events of a real person, though a novel must, above everything, keep a rising dramatic arc. I can compress events for dramatic intensity, change four geographical moves to one, or combine three friends into two. But so little is known about Camille that I had to use the few words I could find and fill in a great deal. I think the young impoverished Claude would have seen this upper-class girl as a sort of mystery, and so as I wrote she came to the page through his eyes. And then there is the important realization that real people do not always seem the same through the eyes of those who knew them or biographers who look back at them. To some biographers, for instance, Charlotte Bronte was a generous saint; to others she was caustic and critical.

Claude and Camille starts and ends at Giverny. Did you use the place where Monet painted his famous water lilies as a point of reference for readers who might not be acquainted with the artist's life?

Yes, I did use Giverny as a reference point and also to give the older Monet the chance to ask himself exactly what had happened so many years ago when he had lost Camille, and also why she had haunted him ever since. To be very honest, I was not particularly fond of the water lily paintings but loved the other landscapes etc. that he did in his youth. It was when I went to Paris to research the book that I visited the Marmottan Museum and first really looked at the huge water lily and other flower paintings. I was emotionally overwhelmed and burst into tears. I was very shaken; I felt myself drowning in flowers, water, and reflected sky. In my opinion, the water lily paintings were a search for meaning and the eternal. He had lost both his wives by that time, his son, and a beloved stepdaughter; Europe had been ravaged by the Great War or would soon be ravaged, and he was losing his eyesight. As a result, the water lily paintings are very intense.

When Marrying Mozart was published in 2004, many reviewers commented on your background as an opera soprano. How does your love and knowledge of music affect your writing? Do you consciously attempt to give your prose a musical cadence?

Oh yes, I hear cadence in the lines. Music has affected me profoundly and I have music in every book I write. Marrying Mozart was such a happy book to create; I listened to all the music he wrote when he first knew the four Weber sisters (before he finally married Constanze Weber) and I structured the book a little like Le Nozze di Figaro which I had known since childhood. I certainly know what it feels like physically to sing opera! It's deep in me.

You are working on a sixth book about two famous poets. Who are they and what are the challenges of writing another novel?

I am well into the second draft of a new novel set in Victorian London about the love story of the poets Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning. Elizabeth was an invalid of forty and still beautiful when Browning found her in her father's house and snatched her away to live in Florence with him. The big challenge is that each book has its own problems, but I hope I have learned not to write myself into a corner for a year before seeing clearly that it is a corner.

You've been writing historical fiction since Nicholas Cooke in 1993. Why were you attracted to this genre and what are the gifts necessary to succeed?

I was first drawn to historical fiction by a place and time. I loved Elizabethan theater and life; I had been reading about it since I was twelve years old. I think an historical novelist needs a profound love of and curiosity about certain historical figures and a complete devotion to bringing them to life on the page so that they are as real as your neighbor. Ironically, this also takes a certain irreverence. You have to sort of run in and grab that character and make them live and breathe, and at some point, you have to put your history books in the other room and take a leap of faith, bringing your character to life.

Your writing mentor was Madeleine L'Engle. How important was her influence when you were launching your career and what was her best piece of advice?

I met Madeleine at a writer's workshop and read a Biblical piece I had written for her. She loved it and I asked her (with my heart in my mouth) if she would read my unpublished novel, Nicholas Cooke. She did read it and loved it. When I finally sold it, she sent me a huge bunch of flowers and not only gave it a [jacket] blurb but brought me several other people who blurbed. Her most important advice was, 'Listen to your characters.'

You have traveled to great European cities mentioned in your novels: Vienna and Salzburg for Mozart, Paris and Giverny for Claude and Camille, and London and Stratford for The Players: A Novel of the Young Shakespeare and Nicholas Cooke. Did visiting these places change your impressions of the artists you were researching?

No, it didn't change my impressions, but it gave me a sense of the physicality of each place. Central Vienna and Salzburg are small, and the original walled city of London was but a tiny section of London today. Some of the old gates are still there, or parts of them. The length of time it takes to get from one street to another is important. Also English damp is amazingly damp and really gets in your bones. It was thrilling to stand where Mozart was married and walk through the rooms where Shakespeare ran as a little boy.

What is the value of historical fiction?

As I said before, to bring the past to immediate life. The people of centuries ago felt the sun and wind as we do. They fell in love and felt jealous. They had different thought patterns in some things because their circumstances were different: they had no electricity and much less medical care. They mostly believed in God as clearly as we know where our front door is. They were superstitious. In Mary Renault's work, the gods are walking around, rumbling beneath the earth.

Do you complete all your research before you write the first line or do you do a bit of research and dive in, filling in the gaps along the way?

I know a little about the character when I start and then I fill it in with research, both as I go and at the end. I only remember writing the beginning of Nicholas Cooke; I wrote a paragraph about a boy theater apprentice in London around 1593, hearing the plague carts around him and being frightened of them. I knew a lot about the way theater worked back then and a fair amount about the times because I had always loved them but I never expected to write about them. The whole book grew from that.

What advice would you give to fledgling historical novelists?

Study history and social history, learn everything you can, and then go and create your own living beings from your own emotional experience. If one person gives you a certain piece of feedback about your writing, tuck it in your mind. If three people say the same thing, listen very seriously.

Cowell's paperback is from Broadway Books/Crown.

For further information about the author, visit www.stephaniecowell.com