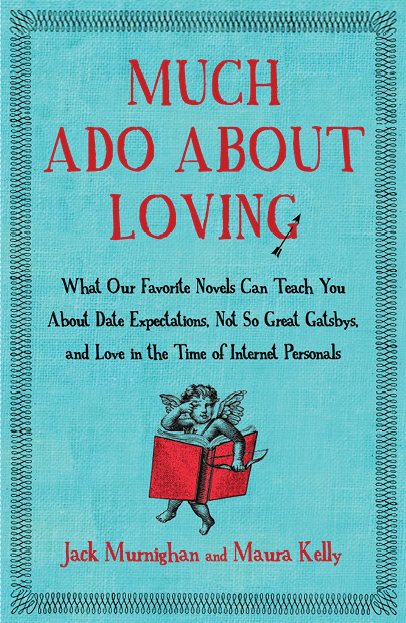

Where would David Foster Wallace have turned for help with his love life? He "may have been sympathetic to the just-published Much Ado About Loving, in which the writers Jack Murnighan and Maura Kelly plumb great literature for relationship advice," according to the New York Times Book Review. Publishers Weekly similarly praises the book as "a clever, amusing hybrid of lit crit" and personal essay, and Elle recommends it over conventional self-help volumes for anyone "seeking advice to bolster a love life more tragic than a Thomas Hardy novel." Both Kelly and Murnighan have made a living, at times, musing over the vagaries of the human heart, and have put in their time in the dating trenches of New York City. They also both have a deep and abiding passion for classic literature; he has a Ph.D. in medieval lit from Duke, and she received an MFA after studying at Hollins and George Mason. In Much Ado About Loving: What Our Favorite Novels Can Teach You About Date Expectations, Not So-Great Gatsbys, and Love in the Time of Internet Personals, they discuss their favorite novels while also talking about the insights those books have given them into their personal lives: their flirtations, infatuations, disappointments, desires, and even their romantic successes. I spoke with Kelly about the intersection of love and literature.

Why did you want to write this book?

Both my coauthor Jack and I are passionate about fiction; we've also had our fair share of dating difficulties. Almost as much as living has, books have taught us plenty about love -- what it means to be in it, what kinds of crushes are ill-advised, which kinds of people are worth risking yourself for, which kinds you shouldn't get too worked up about, and so on. Reading was an escape from the world, but it was also, as it turned out, a way of preparing ourselves to be in it.

More specifically, though, whenever Jack and I would get together, we'd talk about two things: the novels we were loving, and the people we were loving (or trying to love). Usually, my personal conundrums were a little more urgent, shall we say, than his, and Jack always had excellent advice for me. Just about as often, he'd take a book down off his shelf to help demonstrate a point he was trying to make. For instance, I mused to him once about how certain women seem to be so much more ineffably captivating than others; what, I wondered out loud, was their magic? Unexpectedly, Jack actually had an answer to that question -- and he pointed me to War and Peace to help explain it.

He had such good insights that I began to think, "Hmm, I should bottle Jack." And then I began to think, "Hmm, he should write a book about how literature can change your love life." Eventually, we decided to write it together.

Which of the chapters that you wrote do you hope most resonates with people?

At the risk of sounding overly earnest, I really hope that every chapter is helpful for somebody -- and that most chapters are helpful for everybody.

But in the first chapter, I talk about how it used to be that I never wanted to be a part of any club that would have me as a member (to paraphrase Woody Allen by way of Groucho Marx). Any two-person romantic club, I mean. To put it another way, I only ever seemed to like people who didn't like me back. You know -- I was into the tall, dark, handsome types who couldn't care less about me. It took me a long time to figure out why I was keeping myself in that kind of a Catch-22 limbo -- and Sylvia Plath's heroine in The Bell Jar helped me untangle my own knotty psychology. It wasn't until I realized that people who were interested in me weren't automatically deeply unappealing that I was able to date in any meaningful way.

I spent a lot of lonely years banging my head against a wall, and I hope that other people will read this book -- and maybe that chapter in particular -- and not have to suffer and agonize quite as much as I did.

I'm also curious to see how people react to my chapter about Revolutionary Road. It's about how bad it is to date people like Frank Wheeler, the protagonist of that book -- people who have achieved a certain amount of genteel success, but have never tested themselves in any real way, or taken any meaningful risks; people who think they're better than everyone else just because they have a certain artistic sensibility. New York is home to a lot of those types -- people who think that just because they have good taste in restaurants and books and movies that they could be the next Hemingway or Warhol or the third Coen Brother. Those people are often a terrible mix of arrogant and insecure, and not pleasant to be in relationships with -- that's been my experience, as it was April Wheeler's. I wonder what others think.

What loves lessons described in your book were the hardest for you, personally, to learn?

One of my chapters, inspired by a certain Faulkner novel, is called "Lightbulb in August: How to have a clue when he's just not that into you." In it, I talk about how a lot of us modern women use feminism to basically explain away a guy's otherwise unacceptable behavior. I can't tell you how many times I'd find myself saying, "Oh, I guess the reason he hasn't called is because he doesn't know whose move it is -- and being the indomitable modern woman that I am, I'll take the lead!" There's nothing wrong with steering things, of course, particularly if you feel confident about putting yourself out there. But when you don't feel comfortable (as I often didn't) -- but if you're forcing yourself to be more aggressive than you want to be, or doing all the planning or the asking -- that may not have anything to do with his progressive feminist ideas. Maybe it's more that he's not that interested (but is perfectly willing to go along with things for the time being, perhaps especially if he's getting sex out of the deal). When you meet someone and there's good chemistry, the give and take feels a lot more natural; you're not always talking yourself into being more impulsive or pro-active than you want to be all of the time. I'm tempted to say that the most feminist thing you can do is to hold out for a relationship in which you're being treated exactly like you want to be.