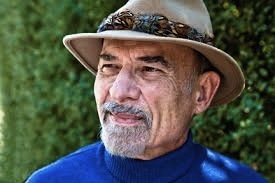

Irvin D. Yalom is as well known a writer of fiction as he is of non-fiction. His novels include the famous When Nietzsche Wept (a tour de force rendering of the relationship between Freud's mentor, the renowned Dr, Joseph Breuer, and the philosopher Frederick Nietzsche), The Schopenhauer Cure and the most recent, 2012's The Spinoza Problem.

He is also the inventor of a new non-fiction form, in which the psychiatrist Dr. Yalom describes conversations he has had with some of his most challenging patients. One such is his new book, Creatures of A Day, and Other Tales of Psychotherapy, which was published this year by Basic Books. The best known of Dr. Yalom's non-fiction books is Love's Executioner, which, as well as possessing one of the most compelling titles ever, contains the equally appealing passage from which the title is taken:

I do not like to work with patients who are in love. Perhaps it is because of envy -- I, too, crave enchantment. Perhaps it is because love and psychotherapy are fundamentally incompatible. The good therapist fights darkness and seeks illumination, while romantic love is sustained by mystery and crumbles upon inspection. I hate to be love's executioner.

I spoke with Yalom recently, interested in why he writes both fiction and non-fiction. I wanted to ask him which of these forms he prefers, and what does each form require of him that the other does not.

IY: I have a lot of blurring between fiction and non-fiction in so many of my works. For example, my first novel, When Nietzsche Wept, has a great deal of non-fiction in it. I didn't create many characters at all. Almost all of them are historical characters that actually existed. Now, I consider that almost like having written fiction with training wheels. Everything, historically, was already there.

But the next novel, Lying On The Couch was entirely made up, and I felt then that, really, I was jumping off into fiction. I'm reading that novel now again, though, for a memoir that I'm writing, and I'm amazed by how much non-fiction there actually is in it. A lot of instances from my past life that I attribute to the characters. Many things from my own past are in there. Even some of the characters' names... I changed them around, of course, but some of them are very similar to the names of people I actually have known.

Something like that takes place in my non-fiction stories, too... the blurring, I mean. Those stories all have fiction in them. First of all, I have to change almost all the details of a physical, factual nature in the story, in order to protect the identity of the patient. I've changed men into women. I've made tremendous alterations in the characters. In essence, though, the main character remains as he or she really is, and I will have changed certain features of their appearance or personality.

Incidentally, despite all this, I ask each of the people, on whom patient conversations have been based in a particular story, to read my final story. All of them have approved.

But here's something about those stories. One of my most read books is actually a textbook titled Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy. The individual stories in that book, of patients in group therapy, are true. I really was trying to find my wings as a writer at that time, and I am certain -- I have no question in my mind at all -- that the reason that book is so successful is that it contains those stories, which I bootlegged into the book. Legions of students have told me that what they really like are the stories. They can put up with a lot of dry theory (Yalom grins.) if they know that another story is coming around the bend in a few minutes.

TC: What impact has your being so well known as a writer had on your practice as a psychiatrist?

IY: I'd love to write about that some time. Now, literally every patient I see has come to me because of something I've written, and that does have a significant impact upon the course of the therapy. It makes me into a bit of a larger-than-life figure for the people I see, and maybe potentially it even gives me more power to do good, as long as ultimately I can get past their need to see me as a special sort of figure. I don't want to be idealized by a patient because of what I've written.

TC: Is writing fiction more, or less, difficult for you to write than non-fiction?

IY: I enjoy writing fiction more. I have had great experiences... adventures! When I've been writing a novel. And now, my inclination is to continue writing only fiction. You know, I'm a compulsive reader of fiction. I fell in love with novels when I was a teenager. My wife Marilyn and I... our initial friendship began because we are both readers. I've gone to sleep almost every night of my life after having read in a novel for 30 or 40 minutes. I'm a great reader of fiction, and much less so of non-fiction.

TC: Would you consider writing fiction that does not have a basis in psychiatry? Would you go farther afield?

IY: I can imagine doing that, but even then, my work would be categorized by its looking at internal issues, by how people think, by what consciousness is like. I don't think I could write a mindless detective story.

In a new afterword for the 2012 re-release of Love's Executioner, Yalom writes,

"I had always wanted to be a storyteller. As long as I can remember, I've been a voracious reader and somewhere in early adolescence I began yearning to be a real writer. That desire must have been percolating on the back burner as I pursued my academic career, for as I began writing these ten stories [for Love's Executioner] I sensed I was on the way to finding myself."

As fictional elements pervade his non-fiction, and as actual facts determine much of the action of his fiction, Yalom's devotion to both is clearly evident, and functions on equal terms, the one with the other.

Terence Clarke's latest novel The Notorious Dream of Jesús Lázaro was published earlier this year. He is director of publishing at Astor & Lenox.