Occasionally, wretched excess is quite beautiful, and an example -- many examples -- can be found amply presented in "Maharaja: The Splendors of India's Great Kings," an exhibit currently up at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, through April 8. Until now, I had not seen an entire carriage, the team for which would be four horses, made almost entirely of silver. But the Maharaja Bhavsinhji II of Bhavnagar had one such made for him in 1915 by the Fort Coach Factory of India, the finest carriage-maker of its time on the Indian sub-continent. The structure of the carriage is made of iron, but every metal surface -- including even the bolts, the springs... everything -- is clad entirely in silver. The carriage is also decorated with many delicate representations of flora and fauna, all done with impeccable care.

It is one of the most remarkable objects I have ever seen.

Used courtesy of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Not to put too close a political reading on this carriage, but it is also one of the finest representations of disregard for the welfare of one's subjects that I can imagine. The fact that it is so intensely handsome a vehicle does little to alleviate one's wonder at how Bhavsinhji's subjects lived. I assume that they were mostly rural farmers or shopkeepers who were eking out a very slim living from their endeavors. And I assume that, since we're talking about India, there were a great many of them.

That minor caveat having been considered, one can turn his attention to the amazing wealth -- monetary and artistic -- represented by this show.

Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, 1911

National Portrait Gallery, London. Used courtesy of the Asian Art Museum,

San Francisco

Prior to the English annexation of India in the nineteenth century, there were many dozens of kingdoms in the sub-continent, each of them governed by a maharaja (or, depending upon the regional language being spoken, by a raja, rana, rao, maharana, maharawal, maharao, nawab, nizam, etc.) Various political or marital arrangements, intrigues and wars had resulted over the millennia in these kingdoms, and some of them were among the most splendid in the world.

There were strict expectations for the maharajas. Writers Anna Jackson and Amin Jaffer describe, in this exhibit's fine and very beautifully illustrated catalogue, what these duties were:

India's rulers were expected to exercise appropriate behavior, their royal duties or rajadharma encompassing the protection of their subjects, the adjudication of disputes and the ministering of justice and punishment... Kings were expected to be wise and benevolent, and to be fierce warriors and skilled hunters. India's rulers also exercised their rajadharma through their patronage of religious practitioners and institutions, poets and musicians, architects, artists and craftspeople.

They were also expected to be great ceremonial leaders who exhibit true majesty and presence. Thus the extraordinary luxury and often great beauty of everything in this exhibit.

Almost all the graphic and plastic arts are represented here. For me, the real interest lies in the many paintings, mostly by Indian artists and some by Europeans. The skill at showing scenes almost maniacally crowded with people and animals (elephants, usually) with delicate clarity, fine attention to composition and beautiful color is exemplified by a small painting titled "Procession of Maharao Ram Singh II of Kota," from about 1850.

Procession of Maharao Ram Singh II of Kota, c. 1850.

Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Used courtesy of the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

In her essay in the catalogue about such a procession, Joanne Punzo Waghorne points out that "however extravagant or even baroque, these displays were never frivolous. They were the rituals that kept the royal body politic compelling for its subjects." Just so is the grandeur compelling to the viewer of this painting, the complexity of design and colors of which demand your attention. The figure of the beautiful woman dancing for the maharao's pleasure while borne up on the tusks of the royal elephant is a spectacle the likes of which can barely be imagined.

Necklace commissioned by Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, 1928.

Cartier, Paris. Used courtesy of the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

As you can see from the photo above of Maharaja Bhupinder Singh, jewels in great quantity were a mark of the leader's majesty and otherworldly grandiloquence. In 1928, this same man commissioned a necklace for his wife from Cartier of Paris that was made with platinum, diamonds, yellow zirconia, white zirconias, topazes, rubies, smoky quartz and citrine. Were she to be wearing some of the royal clothing exhibited in this show, this necklace would surely adorn one of the most spectacularly dressed women in the world.

After the arrival of the British, the maharajas lost most of their real political power. But they were retained by the British for important ceremonial reasons, primarily to support the empire's claim on India. Some of the kings and their wives became darlings of the European social set, and their palaces were often furnished in the most contemporary European design. They would have been educated in Europe and would have traveled frequently to European capitals.

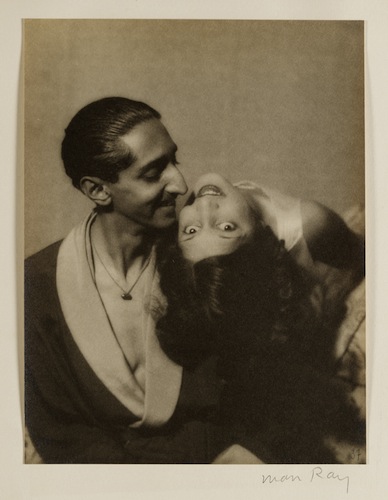

One such couple were the Maharaja Yeshwani Rao Holkar II and Maharani Sanyogita Devi of Indore. They became friends with the photographer Man Ray, who often photographed them.

Maharaja Yeshwani Rao Holkar II and Maharani Sanyogita Devi of Indore, c. 1930.

Man Ray, Al-Thani Collection. Used courtesy of the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco.

This exhibit was originally mounted by The Victoria and Albert Museum in London. One of its great pluses lies in the fact that it introduces the viewer to a remarkable world of which he may not have known prior to going to the show itself. Many of the objects displayed are close to unbelievable. I would not have missed seeing them for anything.