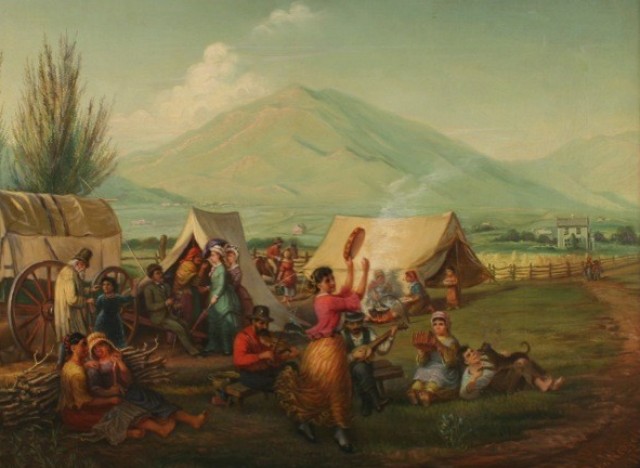

A mislabeled painting is one of the most telling artifacts in Mormonism's long and sometimes fractious history with the American people. In 1876, a work by Mormon immigrant from Scandinavia Danquart Anthon Weggeland was accepted for the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. It came to be known as Campsite Along the Mormon Trail (its current catalog listing). Mormon viewers readily saw themselves in the scene of west-bound travelers, with their wagon and pitched tents, dancing and playing music with cookfires and a mountain peak in the background, all portrayed by a Latter-day Saint upon the heels of the forced exodus from Illinois.

The painting's more subtle elements poignantly evoke the Mormon experience. Parasolled ladies mingle with a suited gentleman in front of a crude camp tent, while a mixed gender band plays music and a boy romps with a puppy and others prepare food, all in bucolic splendor.

But the scene is not deserted prairie or rugged desert -- it is fertile farmland with fences and fashionable homes near to hand. It is, therefore, more like a scene of peasants making merry outside the gates of a rich man's feast, than of the children of Israel fleeing Egypt for a promised land. The effect is a sense of proximate exile, tenuous gaiety in the face of exclusion. But as close examination reveals, the painting wasn't about Mormon pioneers at all. Weggeland had clearly labeled it "Gypsy Camp." The Mormon experience of exile and alienation made them all too ready to read themselves into a scene that captured the ambivalence of their own predicament: was it Eden or Bablyon they were leaving behind? Was this the exile of the disposed, or the triumphal march toward a better, more secure Zion?

Representations by detractors were less benign, but created their own paradox. The cause of conflict and the ensuing Mormon exodus were varied -- but one factor in particular complicated the Mormon problem, created unique forms of anxiety, and led to strategies of representation with long-lasting consequences. Unlike Native Americans, blacks, "Mohammedans," Jews or other unpopular groups of the era, Mormons were not an ethnic group -- or like the Catholics, readily identified with an ethnic group (the Irish). Visible -- or imagined -- signs of ethnicity in these other cases provided a ready mode of identification. Forewarned is forearmed. And ethnic differentiators could easily be exaggerated to provide a sense of distance, insulation, and security from the threat of contamination, or distorted to the point of dehumanization, to ease the guilt of violence against kindred human beings. But Mormons were didn't cooperate with such practices, because they were disarmingly like other Americans. Popular fiction of the era reveals an alarmist response to Mormons usually reserved for heretics, a fifth column, shape shifters or other infiltrators who threaten the body politic from within, bypassing rules of fair play by which they identify themselves as enemies. "The Viper on the Hearth," is how Cosmopolitan Magazine characterized the threat "to every American."

So popular writers responded with their usual resourcefulness, employing two strategies. In the first instance, Mormons were made to employ, without exception, modes of coercive conversion. The implicit message was, "don't worry: you need not fear being won over to this people. The values you embrace are not susceptible of rational defeat." The motif of the evil eye, the hypnotic gaze, persisted through dozens of treatments and even into the silent film era ("Trapped by the Mormons"). More blatantly, heroes from Buffalo Bill to Sherlock Holmes and dozens more confound the Mormon villains by rescuing their victims -- men as well as women -- from drugged stupors, underground prisons and guarded mountain cities. Such melodrama has largely faded from Mormon treatments in literature -- though the "cult" canard raises the old specter in only slightly more respectable fashion.

More interestingly, perhaps, was the 19th-century device of constructing a distinctive ethnicity where none existed. Relatively few enough had actually seen a Mormon, apparently, that writers could consistently and credibly conjure images of Mormon "orientalism," or just a vaguely limned "otherness." Salt Lake was "as Oriental as Damascus" (Thompson Dunbar). Jack London's character notes "they ain't white ... they're Mormons" ("Star Rover"), Dan Coolidge writes of their "strange, foreign look" ("Fighting Danites") and illustrators depicted them as caped, Mediterranean looking cavaliers or as Amish-looking yokels who spoke Elizabethan English. Science was invoked to sustain the dozens of similar depictions, when two academics argued in an 1861 meeting of the New Orleans Academy of Sciences meeting that Mormons were already developing into a physiologically distinctive "new race." Such seeming absurdities turn out to have foreshadowed -- and no doubt, facilitated -- a rather startling state of affairs: In the current edition of the Harvard Encyclopedia of Ethnic Groups, "Mormons" have their own entry.

And so we arrive at the converse of our first story. In that instance, Mormons wanted to see exclusion as a holy hegira, but their way was fraught with nostalgia for the homeland left behind. In the second tale, detractors impose a radical difference on Mormons that achieves a canonical status -- which Mormons came to embrace. At least until politics raised the question of their respectability to the forefront, and they fought their way to acceptance and "normalcy." Now, in the afterglow of Romney's respectable showing, one finds unease among some in the ranks of Mormons. They ask: Is distinctness or integration the greater burden?