Dogs are just domesticated wolves, brought in from the wild somewhere in Asia back in the Pleistocene. Dogs and wolves can and do interbreed, and scientists consider them the same species. Given the lack of biological difference between the two, it's interesting how differently we perceive them. Whereas dogs are man's best friend and the archetype of loyalty, folklore has given us the Big Bad Wolf and the wolf in sheep's clothing.

Domestication makes all the difference, of course, and we humans have always been leery of large carnivores that kill our livestock and are capable of killing us. Still, the viciousness and thoroughness of past wolf-extermination campaigns in this country, and the lingering antipathy towards them in the few places where they still exist, seem out of proportion to the risk they pose to livestock and people.

In the first half of the 20th century, we came very close to scrubbing wolves off the face of the conterminous United States. This was no accident. In 1750, close to 200,000 wolves roamed the land, occurring in each of what would become the lower 48 states. With each passing year, that number sank, plunging precipitously between 1900 and 1920 as Congress officially sanctioned the Bureau of Biological Survey to shoot, trap, and poison wolves to extinction. Sarah Palin has nothing on these guys--they were brutally effective. Ironically enough, the extermination was complete in the world's first national park, Yellowstone, where every last wolf was dead by 1930; there, as elsewhere, the wolf-elimination program was intended to boost deer and elk populations.

That plan worked, probably better than anybody expected or even hoped for. The country's white-tailed deer population exploded, from roughly 5 million in 1960 to 30 million in 2000, while the number of elk in Yellowstone shot up almost an order of magnitude, from 3,000 to 20,000.

Good news for hunters, but bad news for our country's ecosystems. Not surprisingly, the deer and elk got comfortable in these newly wolf-free habitats. Not only were there more of them, but they began brazenly foraging in areas, like streamside vegetation, that would have been too dangerous before. Populations of aspen, willow, and cottonwood trees could no longer successfully replace themselves, since their seedlings were getting hammered by the ravenous herds. When the old trees died, there were no younger trees to take their place. The loss of vegetation along stream beds led to erosion of the exposed banks and muddying of the waters. Moreover, beavers, which had been recovering from heavy fur-trapping in the late 1800s, crashed in the 1930s, as the trees they fed upon disappeared. Since the dams beavers build create and regulate wetlands, their disappearance further transfigured the ecosystem. With no competition or predation from wolves, a smaller predator in the ecosystem--coyotes--ran amok.

So went the chain-reactions from this ill-advised eradication program, dramatically altering the form and function of our country's most iconic ecosystem. But it wasn't just Yellowstone and it wasn't just wolves--the loss of wolves, cougars, and grizzlies has changed the face of the West, from Olympic National Park in Washington to Utah's Zion Canyon, from the cottonwood trees all the way down to butterflies and lizards.

Then, in the mid-1990s, something amazing happened. The US Fish and Wildlife Service took 66 wolves from Canada and plunked them down in Yellowstone, over the fierce objections of many locals in Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana. Since 1995, the wolf population of the region has quintupled.

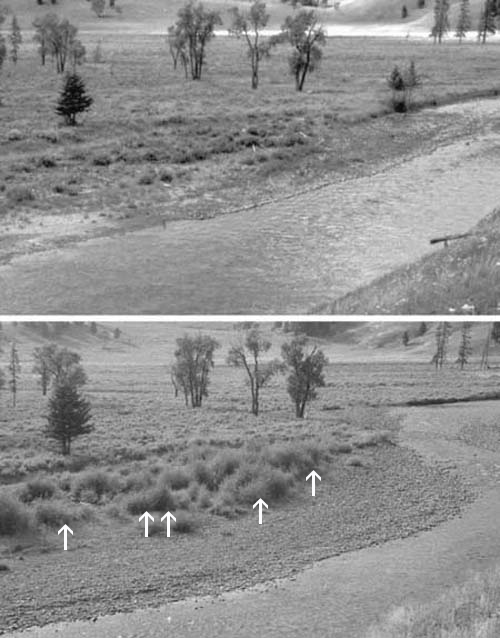

Much of what we know about the importance of wolves in maintaining the integrity of these ecosystems has come from research by Oregon State University's Bill Ripple and his colleagues, who have been studying the ecological impacts of the wolf reintroduction. And the effects have been dramatic. Within three years of the reintroduction, coyote populations declined by 50%. The elk are back down to reasonable numbers, and more importantly, they've regained a healthy level of fear, avoiding high-risk areas like the sensitive stream banks. The aspens, cottonwoods and willows are all coming back, and with them, the beaver. The top photo below, from a paper by Ripple and his colleague Robert Beschta, was taken in 1991; the photo below is from 2002 and illustrates the recovery of streamside cottonwoods after just seven years of wolf presence.

The restoration of the wolves and the subsequent recovery of the Yellowstone ecosystem is one of the greatest conservation success stories of all time. Should we try to replicate it elsewhere?

Absolutely. Since we've already summarized the ecological benefits of doing so, let's just take a look at the possible objections. First of all, wolf attacks on humans are vanishingly rare. Wolves do of course occasionally attack livestock, and this was one of the loudest arguments against putting them back in Yellowstone. In reality, however, the economic threat posed by these occasional events is negligible, especially since the Defenders of Wildlife pay ranchers full market value for wolf-killed calves and lambs (totaling $1.14 million since 1995). Also recall that coyotes are more abundant where wolves are absent, and coyotes are quite efficient stock killers. According to the US Department of Agriculture, of the 190,000 cattle killed by animal predators in 2005, coyotes were responsible for more than half (man's best friend, the domestic dog, came in second with 11.5% of the toll). So most of what's saved, livestock-wise, by killing wolves may be lost--and then some--to corresponding increases in coyote predation. Finally, increased tourist dollars from people paying to come see wild wolves stimulates local economies and more than offsets the impact of any livestock losses on the regional economy. In 2005, nearly 100,000 Yellowstone visitors spent more than $35 million specifically to see or hear wolves.

We still have a chance to restore functionality to the ecosystems conserved in our nation's fabulous national parks. There are viable opportunities for wolf recovery from the Pacific Northwest to Arizona and as far east as New York and Maine. Most Americans seem to like the idea. But the window is closing. Once a stand of trees disappears completely, restoring wolves will not bring it back--the ecosystem settles into what ecologists call a new "stable state," and a priceless piece of our biological heritage is lost.

Visit the Defenders of Wildlife to find out what you can do. The Yellowstone image is taken from WJ Ripple and RL Beschta, 2003. Wolf reintroduction, predation risk, and cottonwood recovery in Yellowstone National Park. Forest Ecology and Management 184:299-313.