(Photo of Wheeldon by Arthur Elgort)

British-American choreographer Christopher Wheeldon's new modern ballet company, Morphoses (whose name connotes change), just finished its second, too-short season at New York's City Center with two programs containing a total of seven short ballets, almost all of them new.

Of all ballet artists Wheeldon (35), one of the most sought-after choreographers in the world these days (many companies perform at least one work by him per season), seems to be trying the hardest to bring ballet back, make it stylish, sexy and popular again. The man, with his enthusiasm, dimpled grin, boyish looks and of course charming accent, is extremely likable. At the beginning of each night, he came onstage and gave a little talk, chatting about some of the pieces on the program, letting us know how nervously excited he was to use music by Gyorgy Ligeti for the first time in Polyphonia, his signature ballet from 2001, and that Commedia, his new comical piece in the style of Italian Commedia dell'arte, involving a sometimes frolicking sometimes more sober set of traveling performers, was made for an upcoming celebration of the anniversary of Les Ballets Russes (about which you may remember an excellent documentary a couple years ago). He explained that each piece would open with a little film segment of the dancers rehearsing or being coached or just living their lives, in order to make audiences more relaxed, make them (particularly the younger generation, un-used to opera-house-formality concert dance) feel like they were just at the movies. "They'll give some of you in the back," he said, "the chance to see the dancers up close." He longs to make ballet more accessible to youth, and feels that showing them what goes on behind the scenes will do that. Finally, he said, with his dimpled grin, he hoped people would attend a free "brunch at the ballet" on Sunday in the theater, in which people could munch on bagels and croissants while watching the dancers rehearse their final performance.

(photo of Fools' Paradise by Erin Baiano)

Wheeldon is so sincere and his efforts so valiant you want him so badly to succeed. I'm not sure how much his program brought audiences closer to dance though. In one of the "filmettes," for example, Canadian choreographer Emily Molnar, instructs her dancers to make sure they have all-important "clarity of intent." It sounded good, but when the actual dance was shown, it was rather long-winded, much of the movement didn't seem to amount to much or contain any discernible meaning, and I saw dancers moving very fluidly, very well, but I wasn't sure whether I saw any of their "clarity of intent" or how to even recognize that. I'd think clarity of intent would mean making clear what that dancer's character or persona wants, what his or her role or objective is in the ballet, but in plotless, abstract ballets, I'm not sure how to assess that or what it even means and the filmette didn't clue me in.

Perhaps ironically, the films were more successful when filmmaker Benjamin Pierce exercised a bit more artistic control - when it became more film-like and not so centered around the dance. In one filmette, promising newcomer and precociously charismatic 15-year-old Beatriz Stix-Brunell is shown studying at her high school, skipping home, eating a snack, doing homework, then donning pointe shoes, ready for her second life. We skip to her older counterpart who, after rehearsal, tosses off her toe shoes and spends the afternoon shopping in the city, exhausted on not being able to find what she wants - something we all can relate to of course - then crashing at a café. The audience laughed; in its own small way the film drew us in to these dancers' personal lives. In another filmette, two dancers simply roll on the ground in extreme slow motion, the camera so close to their bodies, it had a sexily eerie effect. Then, they sat atop a mirror and moved their upper bodies, the mirror's reflection creating all manner of bizarrely stunning shapes. Shouts like "weird!" "cool" and "whoa" could be heard throughout the concert hall. Two older women beside me rolled their eyes, pronounced it "weird" but with a negative subtext. "I guess he's really into the movies," one said. Poor artistic directors: it's hard to please everyone.

So the dances: the program was a fairly eclectic mix, though in the future it would be nice to see some more narrative dances. Program 1 consisted of the cute, theatrical Commedia, Molnar's gorgeously danced but ultimately lacking in destination Six Fold Illuminate, and Wheeldon's Polyphonia, itself a combination of dances, some solos, some duets or trios, some danced in full ensemble, the dancers dressed in purple leotards making stunning shapes with each other, at times their dancing seemingly discordant with the music or each other, then all coming together, in synchronized unison, both the discordance and synchronicity mesmerizing in different ways. Go here to see a clip.

(photo by Erin Baiano, Commedia)

(photo by Rex Keep, of Carla Korbes and Batkurel Bold in Polyphonia)

The second program was far better. It contained two wholly original pieces - Shutters Shut choreographed by the British / Spanish team Lightfoot / Leon, which was set not to music but to the Gertrude Stein poem, "If I Told Him: A Completed Portrait of Picasso," recited by Stein herself, and One, a gorgeously rich male / female pas de deux set to techno music with French-language voice-overs by Jacob Ter Vedhuis. In Shutters, I'd never have thought dancing to a poem would work, but the dancers really found the rhythm in Stein's voice, they worked their arms, legs, hips, torsos accordingly, oftentimes repeating a phrase of movement with, for example, a rapid circling of the arm, the same way Stein's voice repeated a line of spoken word, to hilarious effect. You could kind of "see" her words acted out in the movement, but rhythmically, melodically so, not literally. Go here to see a clip of that dance. In One, danced by beautifully muscular Drew Jacoby and her strong-bodied, long-limbed Dutch partner Rubinald Pronk, the bodies looked like water, the way they undulated, weaving together, flowing in and out of each other.

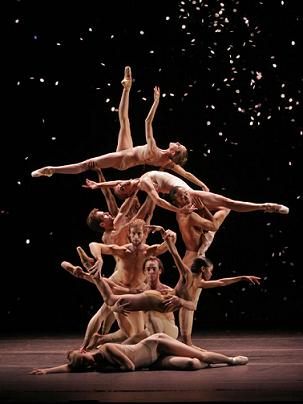

The program ended with another beauty of Wheeldon's, from last year, Fools' Paradise. Set to music by Jody Talbot that is at times melodious at times discordant, like dulcet but somewhat foreboding raindrops growing slowly into a thunderstorm, a group of dancers move by turns in solos, duets, trios, and in ensemble, making awkward but miraculously astounding shapes. Wheeldon, who doesn't yet have his own permanent roster of dancers but culls from a variety of companies, often selects dancers like the seemingly vertebra-less Wendy Whelan, with sinewy muscle tone and long limbs, to evoke the modern, neo-classical angularity of his work. At one point, the long-legged Maria Kowroski bends a knee and wends her arm around her leg, grabbing her foot from its outer edge, then crouches down and pivots on the floor that way. She looks like a spider or a crab. The effect is weirdly tantalizing while connoting a place of lost, contorted, beleaguered souls. Go here to see a clip.

The only piece that seemed out of place to me was Frederick Ashton's ballet Monotones II from 1966 in which three dancers dressed all in sexless white unitards and little white crown-like hats bearing pom poms, bounced around holding hands, looking like joyous, bopping faery-like creatures. The piece was meant as a celebration of landing on the moon, and I guess the bouncing was meant to evoke weightless astronauts, but it looked very dated here. There's a place for Ashton, but in a revival of his oeuvre, not a modern program, and not out of context from his other works. Wheeldon said he included him as an example of the great choreographer's influence on his own style, but (thankfully) that that wasn't at all apparent here and if he wants it to be so, he should spend time up front introducing that ballet and its meaning and impact instead of his own. I think it was more likely included to placate older crowds, but I heard an awful lot of youthful snickers during intermission. You can't please everyone. You have to decide who your audience is and go with it.

In the end, I think there were too many abstract ballets here. Some, like Paradise, One and Shutters, were fun and bizarrely intriguing, but if these kinds of ballets are all you see for two three-hour evenings, then what was initially interesting - these amazing, almost miraculously-produced abstract shapes where you're constantly cocking your head this way and that trying to figure out just what that looks like -- it becomes redundant, loses its ability to amaze. I think people want stories too, interest-sustaining narratives with plots and themes and characters. It may be that modern audience can't apply the suspension of disbelief necessary to buy wholly into the classical full-length story ballets of Petipa's day - with their faeries and fakirs and girls who turn into swans, and evil sorcerers, and unmarried maidens who die and haunt their menfolk in baby blue nightgowns - but that doesn't mean dances can't be made from updated stories. In his last season with New York City Ballet (where he was that company's first resident choreographer) Wheeldon created a hauntingly beautiful ballet, The Nightingale and the Rose, from an Oscar Wilde poem. Why not more of that? Why don't more choreographers find current poems and plays and short stories to convert into a poetry of movement?

Which brings me back to my original critique of Wheeldon's ability to make his process, his work, and ballet in general, more accessible. I went to a program the other night where a choreographer was telling his dancers how he wanted them to dance the role - first, what the character wanted, then how to express that character's desires and wants with a jaunty walk, a flick of the wrist, a bend of the neck. It was so much more understandable to viewers than, for example, the film clip here of Molnar telling her dancers to make sure they have "clarity of intent." I'd think the process involved in creating abstract art is always more difficult for a non-artist to grasp, and it certainly doesn't have to be done - the artist can of course let the art speak for itself. But if you want to let the audience in on the creative process, you've got to let them know where you're going to take them, what your aims are for the piece, how you're instructing your dancers to convey that.

Check out Morphoses for yourself. Video clips, photos, and little blogs kept by the dancers can be found on their website. They're a small company with home bases in New York and London, who tour a bit. Hopefully they'll tour more as they grow.