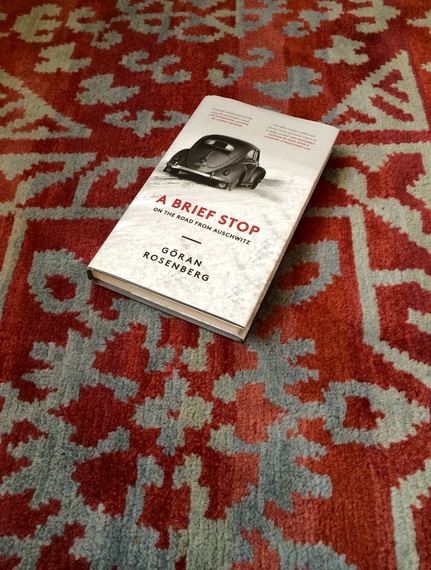

A compelling and poetic reflection on what it took to escape and survive the aftermath of human extinction is Göran Rosenberg's "A Brief Stop, On the Road from Auschwitz." We pick up at the beginning on a child's voice reflecting our own fundamental, most basic disbelief - like watching a hooligan kill a cat, we are left standing, open-mouthed, blinking: "How could...?", "But..why..?", while throughout the book the parent holds our hand, trying to make sense.

It feels and reads like a small story, within the intimacy of a conversation with one's father, yet its ramifications spill and drown with epic. At the heart of it is Rosenberg's need for understanding, as the universal concept of compassion and as the antidote to the incomprehensibility of what occurred. He does not shy away from the horrors, yet his writing is a quiet outrage in which he leaves us the space, and the chance to reach that understanding.

We are allowed the residual feeling of respect for modern Germany's attempts to balance its national admission of savagery with the need to temper an overwhelming sense of guilt. We understand its shortcomings in providing reparations after the fact, because how can one financially measure an experience that was akin to dying once without being able to return to the womb to start again?

This is not a rant but an attempt to overcome for the sake of humanity. He leaves us with a Kiefer-esque impression where layers of monstrosity have hushed but not muted the memories of a time and place. His magnanimity spares us from plain rage, allowing us to feel a historical reverence for what he calls the "slave camp archipelago", so that we too may experience a landscape flattened but still palpitant by 70 years of afterlife.

He is cogent about understanding how the civilising influence of bureaucracy was responsible for the implementation of death: "Precise figures and arbitrary abbreviations are the crowbars of Nazi euphemism". That German high command, while gassing hundreds of thousands, still had to fill in endless paperwork in order to procure specific rations of 1.8 litres of spirits for each of their men, or that at the beginning of the killing process victims being deported could take with them 12.5 kilos of luggage. Why not 2 litres of spirits or 2.5? Why 12.5 kilos and not 15,18? Precision overrode barbarity, disguised atrocity and created normalcy.

His writing is peppered with resonance; his own birth in 1948 signifying "the building blocks of a new world" where "invisible inventories of dreams and expectations" fill the small room of his childhood.

Equally resonant is the role of roads, and their journeys, as vessels of lifeblood and the deciding slip streams of fate for those who lived and died. There is no divine justice or single reason why his parents remained alive, just incredulous luck and fortuitous timing based on the actions of man. So the roads become the divine interventions; their location and cross-currents of possibility together with their means of transport -- trucks, trains, bicycles, cars -- are the spaghetti junction of living where millions, buffeted between the energy, movement and directional decisions of unknown forces, perished, endured and survived the onslaught. And then new roads emerged to allow in opportunity and the warmth of a long- absent sun, even if its light remained dim for many and unattainable for others.

When the unbearable no longer has a name Rosenberg's father writes in his letters to his future wife that it is "boring." Rosenberg doesn't bore us with descriptions of an unimaginable hell; once again, their effect allows us too to understand why the decimation of life is a direct proponent of the psychosis of our planet. His explanations of the survivor syndrome reveal the crux of that psychosis; that the presence of a survivor can become the impediment to survival of a world wanting to be whole. And that the act of surviving rarely turns into the act of living.

This may be a grim subject but it's not a grim book, just a perfectly touching and revelatory read over Christmas. It's nice to keep learning, even when we still don't get on with our in- laws over the holidays.