Well, yes, history does march on, but the evidence that accumulates in its tracks remains behind to jog our memory, and sometimes to people it with ghosts. In 2013, 150 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, the Museum of African-American History in Boston presents "The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Signs of Freedom," a small show brim full of information. This multiple message about the oppression of blacks in America confronts us with three different kinds of historical evidence: abolitionist broadsides, presidential proclamations, and photographs -- paper testaments to the long, tormented history of slavery and racism in this country.

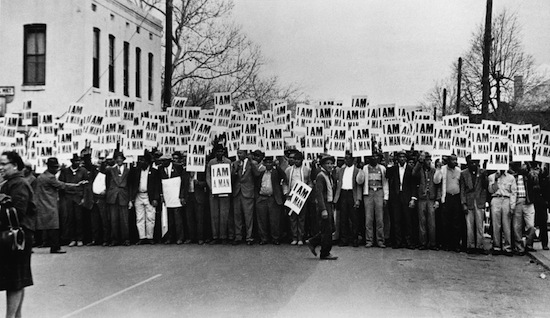

Sanitation Workers assemble in front of Clayborn Temple for a solidarity march, Memphis, Tenn., 1968 ©Ernest C. Withers Trust, courtesy Decaneas Archive

Sanitation Workers assemble in front of Clayborn Temple for a solidarity march, Memphis, Tenn., 1968 ©Ernest C. Withers Trust, courtesy Decaneas Archive

Forty-two of Ernest Withers' photographs of MLK and the civil rights movement offer an insider's view of deceptively quiet moments in those anguished years. An African-American based in Memphis, Withers (1922-2007) recorded the movement from its early days in the 1950s through the tempestuous '60s. His best known photograph is of a phalanx of striking Memphis sanitation workers in 1968, lined up as they prepare to march, each holding up a sign saying "I AM A MAN:" a pyramid of cries for recognition. A second photograph of a few of these men in three-quarter view carrying their signs down a sidewalk is a good-enough report but serves to point up why the stunning first photograph has become the iconic image: There the strictly frontal marchers confront us directly, while above them a complex pattern of words performs a jittery and heart-breaking dance across the surface. A good photographer makes good pictures and pretty good pictures and once in a while something extraordinary -- but nothing in life or in photography arrives at top intensity every time out.

Withers had intimate access to the movement's leaders and traveled with MLK. Most of his pictures here are not as dramatic as those by various photographers of MLK arrested or delivering the "I Have a Dream" speech, but Withers' picture of King riding with the Reverend Ralph Abernathy on one of the first desegregated buses in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1956, as well as other photographs are testimony to a perilous moment in our history.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rev. Ralph Abernathy ride on one of the first desegregated buses, Montgomery, Ala., 1956 ©Ernest C. Withers Trust, courtesy Decaneas Archive

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rev. Ralph Abernathy ride on one of the first desegregated buses, Montgomery, Ala., 1956 ©Ernest C. Withers Trust, courtesy Decaneas Archive

Some show a changing world: there's one of 13 African-American six-year-olds in 1961, all dressed up, happy, and excited while being driven to their first day at an all-white Memphis school as pioneers of desegregation. What the photograph cannot show was how difficult it was to change that world: these children encountered endless racial slurs and unfair treatment in school, nearly half of them left before sixth grade, and some white parents took their children out of the school and moved. At length the neighborhood became African-American alone.

The most explicit and damning evidence comes from words that Withers photographed. News photographs and many others need words to establish content unequivocally -- dead bodies on a street are hard to mistake, but without a caption who can tell whether the scene is in Syria, Mali, Afghanistan or some other troubled spot? Words within photographs are a different matter: They deliver information beyond surfaces and silence. Withers' photograph of a Memphis zoo focuses on a message of reverse segregation: NO WHITE PEOPLE ALLOWED IN ZOO TODAY. (The zoo periodically set aside one day for blacks, who otherwise were forbidden entry.) Elsewhere a white man carries a sign that in effect advocates a new Civil War: SEGREGATION OR WAR. An African-America bears this message: COMMUNIST [sic] CAN EAT HERE/ WHY CAN'T I? And a jerry-rigged covered wagon in a mule train on the 1968 Poor People's Campaign March to Resurrection City in D.C. had inscribed on its canvas: DON'T LAUGH FOLKS, JESUS WAS A POOR MAN.

After Withers died it was discovered that he'd been an informant for the F.B.I., which stained his personal reputation but could not diminish his photographs.

It is virtually impossible to consider the history of the civil rights movement without consulting the photographs, for this was one of the relatively rare times when photographs had a clear impact on events. Withers' influence was probably strongest early on, in 1955, when he was the only photographer to cover the entire trial of Emmett Tills' murderers, which some historians credit with sparking the civil rights movement. In the 1960s, other photographers' harrowing pictures of southern police brutality published in newspapers and magazines worldwide created outrage and pressure on President Kennedy to press for a national Civil Rights Act. [1]

Coincidentally, photographs also played a part in the abolitionist movement and the Civil War. By 1859, the South understood photography's power: When John Brown, that violent abolitionist, was defeated at Harper's Ferry in his attempt to foment a slave rebellion, southern authorities censored all photographs of him and prohibited cameras at his trial or hanging. Then in 1864, when a prisoner exchange returned northern soldiers from the Andersonville prison in shockingly emaciated condition, an incensed Congress looked at medical photographs of these men and, for a little while, considered starving southern prisoners. Widely published engraved copies of the photographs stoked a broad desire for revenge in the northern states. The photographs were shown by the prosecution at the postwar trial of the Andersonville commander, who was convicted and hung; he was the only prison official executed after the war.

The six poster-size abolitionist broadsides in the museum's exhibition grimly hammer home, in words alone, the vicious history of slavery. In 1851, "Colored People of Boston" were cautioned not to converse with watchmen or police officers in that city, for both were empowered by order of the mayor and aldermen to act as kidnappers and slave catchers. This was one result of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, whereby citizens were legally impelled to capture escaped slaves if they came across them; the penalty for failing to do so was an enormous fine. The act so infuriated numerous apolitical and even pro-slavery northerners that overnight they became abolitionists, and its passage inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Others willingly complied with the law. In 1852 in Boston, an escaped slave named Anthony Burns was kidnapped, jailed, tried and convicted. In a broadside the kidnapper offered to sell him for $1,200, but when abolitionists raised the money to buy (and free) him, the kidnapper refused it and Burns was sent back to slavery in Virginia. The case created a furor in Boston and elsewhere in the North; federal troops were brought in to quell protests when Burns was taken to the harbor to be shipped back. A year later the Boston abolitionists managed to buy him out of his second slavery.

Then in 1859 a statue of the late Daniel Webster, was installed at the state house in Boston. Webster was a former senator from Massachusetts who as Secretary of State oversaw the strict enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act, and a broadside lamenting this bronze honor quotes his despised statements of strong support.

Photographs and broadsides are documents, evidence, traces of history. The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation of September 22, 1862, in which Lincoln announced that he would free the slaves on January 1 unless the South surrendered and rejoined the Union, and the Emancipation Proclamation he signed on New Year's Day, 1863, are documents of a different order: They made history, they changed its course, and copies of both are in this show.

When Lincoln signed the second proclamation, he had already been shaking hands for three hours at the annual New Year's Day reception in the White House, and his hand shook slightly. He turned to his Secretary of State and said:

I have been shaking hands since 9 o'clock this morning, and my right arm is almost paralyzed. If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act and my whole soul is in it. If my hand trembles when I sign the proclamation, all who examine the document hereafter will say 'He hesitated.'

And then he signed, with a firm hand. [2]

"The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Signs of Freedom" is at the Museum of African-American History at 46 Joy Street, Boston, until the end of February.

[1] See Vicki Goldberg, The Power of Photography: How Photographs Changed Our Lives (New York: Abbeville, 1991), pp. 203-212, for a discussion of the impact of Charles Moore's Life magazine photographs of police dogs and fire hoses turned on protesters.

[2] Francis. B. Carpenter, Six Months in the White House quoted in Gilson Willets, Inside History of the White House: The Complete History of the Domestic and Official Life in Washington of the Nation's Presidents and their Families (NY: The Christian Herald, 1908) p. 208.